Summer is not without its annoyances — mosquitos, wasps, and ants, to name a few. As the cool breeze of September pushes us back to work, labs across the country are reconvening tackling nature’s hardest problems. Sometimes forces that seem diametrically opposed come together in beautiful ways, like robotics infused into living organisms.

This past summer, researchers at Harvard and Arizona State University collaborated on successfully turning living E. Coli bacteria into a cellular robot, called a “ribocomputer.” By taking archived footage of movies, the Harvard scientists were able to successfully store the digital content on the bacteria that is most famous for making Chipotle customers violently ill. According to Seth Shipman, lead researcher at Harvard, this was the first time anyone has archived data onto a living organism.

In responding to the original article published in July in Nature, Julius Lucks, a bioengineer at Northwestern University, said that Shipman’s discovery will enable wider exploitation of DNA encoding. “What these papers represent is just how good we are getting at harnessing that power,” explained Lucks. The key to the discovery was Shipman’s ability to disguise the movie pixels into DNA’s four letter code: “molecules represented by the letters A,T,G and C—and synthesized that DNA. But instead of generating one long strand of code, they arranged it, along with other genetic elements, into short segments that looked like fragments of viral DNA.” Another important factor was E.coli‘s natural ability “to grab errant pieces of viral DNA and store them in its own genome—a way of keeping a chronological record of invaders. So when the researchers introduced the pieces of movie-turned-synthetic DNA—disguised as viral DNA—E. coli’s molecular machinery grabbed them and filed them away.”

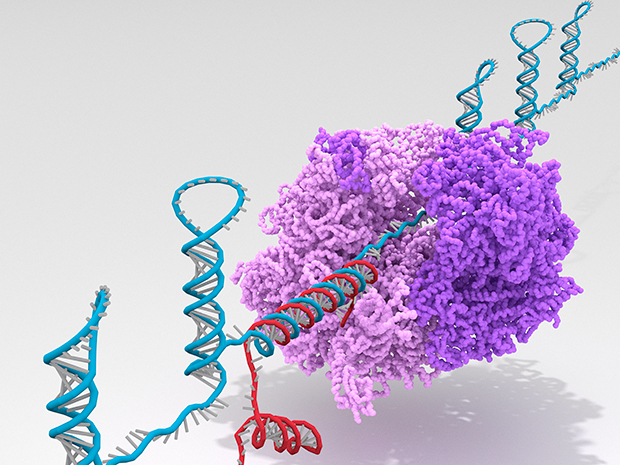

Shipman used this methodology to eventually turn the cells into a computer that not only stores data, but actually perform logic-based decisions. Partnering with Alexander Green at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute, the two institutions collaborated on building their ribocomoputer which programmed bacteria with ribonucleic acid or RNA. According to Green, the “ribocomputer can evaluate up to a dozen inputs, make logic-based decisions using AND, OR, and NOT operations, and give the cell commands.” Green stated that this is the most complex biological computer created on a living cell to date. The discovery by Green and Shipman means that cells could now be programmed to self-destruct if they sense the presence of cancer markers, or even heal the body from within by attacking foreign toxins.

Timothy Lu of MIT, called the discovery the beginning of the “golden age of circuit design.” Lu further said “The way that electrical engineers have gone about establishing design hierarchy or abstraction layers — I think that’s going to be really important for biology. ” In a recent IEEE article, Lucks cautioned readers about the discovery of perverting nature which can ultimately lead to a host of ethical considerations, “I don’t think anybody would really argue that it’s unethical to do this in E. coli. But as you go up in the chain [of living organisms], it gets more interesting from an ethical point of view.”

Nature has the inspiration for numerous discoveries in modern robotics, and has even created its own field of biomimicry. However, manipulating living organisms according to the whims of humans is just beginning to take shape. A couple of years ago, Hong Liang, a researcher at Texas A&M University, outfitted a cockroach with 3g backpack-like device that had a microprocessor, lithium battery, camera sensor, and electrical/nerve control system. Liang then used her make-shift insect robo-suit to remotely drive the waterbug through a maze.

When asked by the Guardian, what prompted Laing to utilize bugs as robots, she explained, “Insects can do things a robot cannot. They can go into small places, sense the environment, and if there’s movement, from a predator say, they can escape much better than a system designed by a human. We wanted to find ways to work with them.”

Liang believes that robo-roaches could be especially useful in disaster recovery situations that maximize the size of the insect along with its endurance. Liang says that some cockroaches can carry five times their own bodyweight, but the heavier the load, the greater the toll it takes on their performance. “We did an endurance test and they do get tired,” Liang explained. “We put them on a treadmill for a minute and then let them rest. If the backpack is lighter, they can go on for longer.” Laing has inspired other labs to work with different species of insects.

Draper, the US defense contractor, is working on its own insect robot by turning live dragonflies into controllable undetected drones. The DragonflEye Project is a deviation from the technique developed by Laing, as it uses light to steer neurons instead of electrical nerve stimulation. According to Jesse Wheeler, the project lead for Draper, he says that this methodology is like “a joystick that tells the system how to coordinate flight activities.” Through Wheeler’s “joystick” he is able to control and steer the wings inflight and program coordinates to the bug for mission directions via his own attached micro backpack that includes a guidance system, solar energy cells, navigation cells, and optical stimulation.

Draper believes that swarms of digitally enhanced insects might hold the key to national defense as locusts and bees have been programmed to identify scents, such as chemical explosives. The critters could be eventually programmed to collect and analyze samples for homeland security, in addition to obvious surveillance opportunities. Liang boasts that her cyborg roaches are “more versatile and flexible, and they require less control,” than traditional robots. However, Liang also reminds us that “they’re more real” as ultimately living organisms even with mechanical backpacks are not machines.