It spanned over 120 feet and took up a considerable area inside the already overpacked robotics section of the Las Vegas Convention Center, leaving many to wonder, ‘What on earth is a tractor doing at CES?’ Ever the since the acquisition of the artificial intelligence startup Blue River Technologies for $305 million, John Deere has been betting its future on data-driven agriculture. Explaining the presence of the enormous green combine on the show floor Laurel Caes of John Deere declared, “It’s a great chance for those in the tech industry to visit withthem and to learn more about how their food is produced and the important role technology plays and will continue to play in putting food on their tables.”

Recently, I hosted Charlie Andersen of AGR Augean Robotics (a ff VC portfolio company) at RobotLab to dig into the AgriTech market. Andersen worked for Deere’s largest competitor Case New Holland (CHNi) after business school and knows the industry from the ground up as a child of a multigenerational farm. After analyzing Blue River and the wider unmanned marketplace for CHNi, he “concluded that autonomy is a force for new market disruption within agriculture, meaning that it is a force best commercialized by startups, so I decided to start a robotics company focused on agriculture.”

AGR is one of the few systems actually working in the fields, while other upstarts are still tinkering indoors. Andersen exclaimed, “Roughly 2 million US farms produce about $400 billion in revenue annually – on a revenue basis, half of the output is crops, and half is livestock.” In his opinion, livestock and grain productions are already on track to becoming fully automated. “Livestock production is often fairly mechanized and in some cases automated (robotic milking parlors for example). Meanwhile, about one-quarter of US farm output is grains – corn, soybeans, wheat, etc. and other field crops like cotton – these crops are very mechanized, with little in the way of labor in their production – this is where Deere, CNHi, Kubota, AGCO, and others focus their marketing and R&D dollars building bigger/better tractors, combines, sprayers, etc,” opines Augean’s CEO. This leaves specialty crop production (e.g., berries, orchards, and vegetables), which accounts for 88% of labor as the low-hanging fruit for disruption. Andersen painted a portrait of aging farmers struggling with increasing overhead and razor-thin margins, forcing many owners to sell their family estates and move production to Central and South America. He shared, “Overall, there is a rising demand for food with growing global population – the irony of the rising population is that as we have more people on the planet we have fewer farmers and fewer people looking to work for farmers. Thus, inputs across the board, from labor to water to fertilizer to machinery, are increasingly expensive and scarce, and generally speaking, growers are looking to do more with less.” Based on Andersen’s remarks robotics is more than the newest equipment, it could be the savior of the United States’ agrarian economy.

While many financial analysts have projected uber growth for agritech, the present reality is stymied by long sale cycles and difficult operating environments. As Andersen explains, “On the challenges side, the average age of a US farmer is 58 and these rising ages correlate with consolidation and an ever-smaller number of larger operators. Simultaneously, the conditions are often very challenging for autonomy, with lighting/weather/field variability/harshness that robots must face and handle consistently over and over again, the diversity of each industry makes finding industries with large TAMs difficult, and developing solutions that scale from one industry to another, is quite difficult.” At the same time, the opportunities could be larger than the other areas of autonomy as unmanned farm vehicles are able to immediately navigate around workers without regulations, pedestrians and other obstacles.

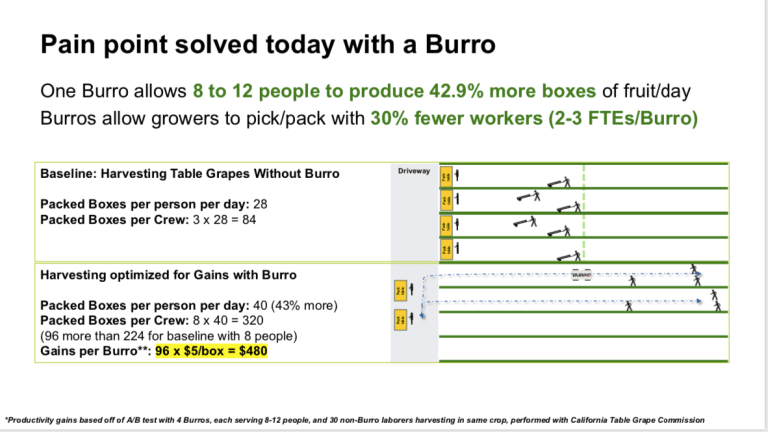

Rather than replacing humans, AGR’s approach is to alleviate today’s agronomy inefficiencies by augmenting farmhands with mechanical donkeys called Burros. “We are doing something different,” boasts the entrepreneur, “taking a stepped or phased approach towards full autonomy, beginning with a collaborative robotic platform called Burro that helps people work more productively today, collects tons of data, over time can be modularly expanded towards fully autonomous farming in a variety of different settings, and which we can get into the market today, not 5 years from now.” After observing how table grapes were picked and collected, Andersen launched a self-driving wheelbarrow to autonomously steer through vineyard rows as a shopping cart for harvesters. He further elaborates, “We’ve found that, like Kiva systems in Amazon Warehouses, if you automate in field transit you can enable people doing high-value/high-dexterity work like picking to be much more productive – a crew of ten people harvesting table grapes with one of our robots running them back and forth can pick 40% more fruit per day, and the payback on one of our robots is accordingly just 30 and 40 days.” Longterm he hopes to translate his success in table grapes to other labor-intensive crops such as berries and orchard fruits. In fact, his biggest worry as a startup is scaling his team to keep up with demand. “Every grower that buys our robots starts asking about 5 other use cases, often in different crops, that we didn’t imagine our Burros going in to, and we have to ensure that our autonomy functions consistently and reliably everywhere,” quips the Chief Executive. He imagines a robotic herd shaping into a complete farming logistics platform over the next few years, “In 5 years, I see our Burro robots forming the core API for many of the future autonomous tasks people would like in specialty crops. By mastering the process of moving from A to B in complex farming settings, with a powerful and modular autonomous platform, I believe we are building a tool carrying platform that can enable autonomous picking, pruning, weeding, spot spraying, and a host of other tasks.”

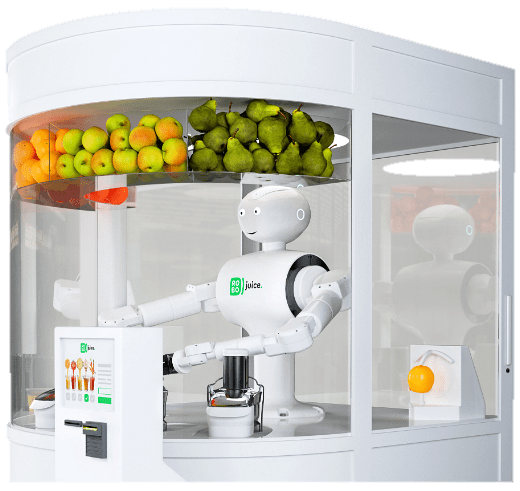

Andersen’s vision is embraced by many other roboticists that see a convoy of logistical solutions from the farm to the table. Last month I was introduced to RoboJuice, a tasty invention by juice bar proprietor Mikalai Sakhno. In the words of the CEO, Igor Nefedov, “I realize that the automation of the food is an inevitable future and I wanted to participate in the change.” Nefedov claims, “Our smoothies will be cheaper, higher quality and little wait.” In light of the recent spat of Robo-downturns such as Zume Pizza, Creator (hamburgers) and CafeX society might not be ready to turn over the kitchen to the bots. Nefedov retorts, “We’re using human-like robots because it’s scientifically proven that people prefer robots that look like them… people will eventually create an emotional connection… that will drive repeat customers.” RoboJuice is still in building mode planning to open the first kiosk to showcase its franchise concept later this year. In the meantime, on a busy Vegas evening at CES last month, I passed a completely empty automated bar, Tipsy Robot. Asking the hostess what’s good, she responded the casino’s nightclub, ‘as the bartender there makes a mean mojito.’