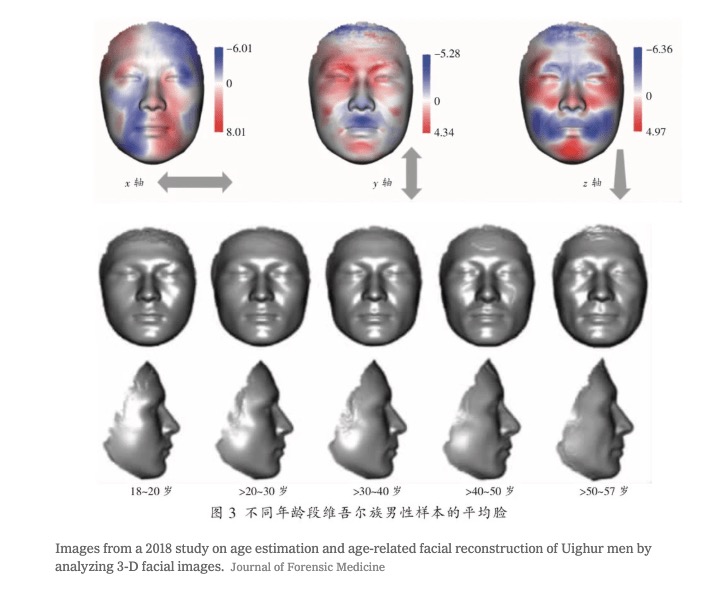

A harem of scantily-dressed women blazed across a recent New York Post cover proudly modeling the latest in affordable cell phone technology courtesy of Pablo Escobar’s brother, Roberto. The tabloid quipped that mobile apps today are more addicting than cocaine. China (among other data junkies) is counting on this dependency to track its citizens (and foreign adversaries). Alarmingly, all of the major telecom providers in the communist state agreed this week to capture the facial identity of new phone buyers, potentially linking online identities to visual scans. Magnifying the announcement, the New York Times revealed how the Asian superpower’s obsession with databasing its subjects has taken a perverse turn akin to the Third Reich’s use of physiognomy and eugenics. The paper reported that China has accumulated the largest DNA database, already populated with 80 million profiles, which is used to recreate facial identities to identify “criminals” and discriminate against minorities. This process, called DNA phenotyping, is not limited to Beijing; in the United States, several police departments have embraced the tool in the name of public safety. Reading these accounts makes one anxious regarding the laissez-faire attitude of America’s tech regulatory environment. At the current rate, it is highly foreseeable that Roomba-like DNA sweepers could be installed clandestinely by municipalities across the country.

For too long online users have been too willing to hand over their personal data in exchange for using mobile services (e.g., Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Google, etc.). As these companies continue to expand their footprints, untethered by regulators, into every facet of their customer’s lives there is a growing revolt. Recently, Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang declared (ironically on Twitter), “Our data is ours – or it should be. At this point, our data is more valuable than oil. If anyone benefits from our data it should be us. I would make data a property right that each of us shares.” He then launched a bold initiative on his website that goes as far as recommending that users should “receive a share of the economic value generated from your data.” Yang’s policy initiative comes on the heels of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) that takes effect in January, creating “new consumer rights relating to the access to, deletion of, and sharing of personal information that is collected by businesses.” The Golden State also plans to add to the 2020 ballot initiatives to expand the CCPA to include wider restrictions on data-mining and the establishment of a state privacy enforcement agency.

The arrest of William Merideth illustrates how personal privacy is colliding with the deployment of robots. The Kentucky man was charged in 2015 with “wanton endangerment and criminal mischief” after shooting a drone out of the sky. The accused claims to have acted in self-defense when observing a quadcopter hovering over his sunbathing teenage daughter. The court eventually agreed with Merideth and declared him innocent of all charges. Since then, the American Civil Liberties Union has championed Merideth’s and all Americans’ rights of privacy over the proliferation of unmanned vehicles. The ACLU’S website states: “Drones have many beneficial uses, including in search-and-rescue missions, scientific research, mapping, and more. But deployed without proper regulation, drones equipped with facial recognition software, infrared technology, and speakers capable of monitoring personal conversations would cause unprecedented invasions of our privacy rights. Interconnected drones could enable mass tracking of vehicles and people in wide areas. Tiny drones could go completely unnoticed while peering into the window of a home or place of worship.”

As popular support begins to cry out for legislation protecting data (and by extension curbing artificial intelligence and autonomous systems) I reached out to Jules Polonetsky, Chief Executive Officer of the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) for guidance on the policy direction. “Data protection has really started to hit a massive changing point in the United States. For a very long time, we had consumer protection law, not privacy law, with the FTC, state regulators, or consumer affairs commissioners enforcing laws that prohibit businesses from engaging in deceptive or unfair practices or activities,” explains Polonetsky. He pragmatically adds, “The U.S. is long overdue for comprehensive privacy legislation. In fact, we’re one of the only democratic countries in the world that doesn’t have one, but we’re rapidly moving in that direction.”

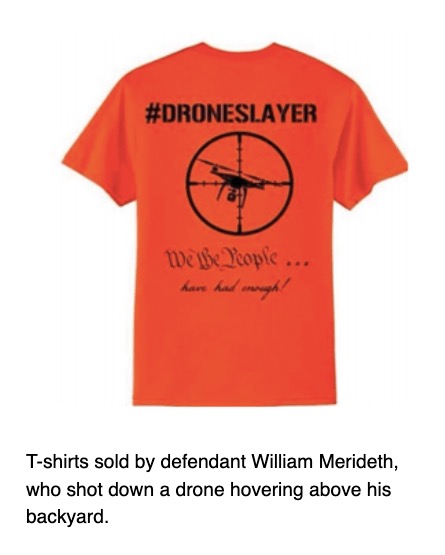

Polonetsky believes that deep learning systems have exasperated the data privacy issue, especially because most people are frustrated in trying to understanding how algorithms work. “Machine learning has only added another element of concern because companies can learn things about you that you didn’t even know. The typical arguments that companies will ask individuals for permission weren’t quite working. People weren’t taking the consents seriously, would ignore them, or they couldn’t conceivably understand what machine learning could do with their data,” suggests Polonetsky. A particular concern to the privacy advocate is facial recognition software: “When my face becomes something trackable and the government or private companies can use it for marketing or have data and intelligence about me, we’ve really lost the last zone. FPF has worked out a set of best practices as a model for facial recognition. We distinguish between identifying people in public and counting how many people are in a space or how they move around a venue.” The principles developed by the FPF carry over to other aspects of unmanned systems in helping to protect use cases that benefit the public good, such as autonomous vehicles. Polonetsky describes, “Autonomous cars are a key area for us to draw those lines – obviously we understand that there is a need for a camera and there is clear value in a camera alerting a driver that they’re looking away from the road for safety, maybe for managing fleets and understanding that a driver has fallen asleep That’s why protecting that data by law could support beneficial uses, but protect against unwanted surveillance and extreme uses by insurance companies or law enforcement.” At the same time, he says we need to bolster communities that take pro-active measures to prevent abuse, “The city of Portland currently has a proposal to ban government and private sector uses of facial recognition. We need to put laws in place that can help allay fears and prevent harmful activity, so as to enable the societally-beneficial uses.”

Polonetsky views regulations positively enabling engineers to focus their inventions on specific use cases, and ultimately forging a better relationship with the public. “My advice to designers and roboticists is that transparency and trust are 90% of the puzzle. If I trust that you’re on my side, I’m eager for you to have my data, to help me, and to support me,” volunteers the privacy advocate. “Companies in a low-trust environment need to figure out how to lean in and ensure that the consumer feels supported and comfortable that how you use their data will improve their life. That doesn’t mean that the company can’t benefit financially while doing so, but are you doing it on the consumer’s behalf?,” questions Polonetsky. He is optimistic that more companies will embrace regulation to build greater loyalty with their users. “I predict you’ll see major tech companies aggressively pivoting in this direction. Although marketing and advertising may be a majority of their income today, their future plans involve smart cities, healthcare, cloud, machine learning, genetics, autonomous vehicles, all areas where you need huge trust. You can see Apple leading in this direction, not only because they decided it’s a human rights value, but because they’re going into the healthcare market. They’re being welcomed because they’ve done work to build that level of trust and confidence, while you see pushback from other companies delving in these fields,” expresses the FPF chief executive.

In Cal Newport’s new book, Digital Minimalism, he confronts the tension between the social good of the Internet and the loss of humanity from overuse. He writes the “irresistible attraction to screens is leading people to feel as though they’re ceding more and more of their autonomy when it comes to deciding how they direct their attention. No one, of course, signed up for this loss of control.” The hunger for data is driving more people to lament Andrew Sullivan‘s famous refrain, “I used to be a human being.” Personally, as a funder of automation startups, my aim is to improve the quality of life, not subvert it. Polonetsky saliently provides a path forward: “Most of us don’t truly want to live disconnected or hide from the world – we just want better control over the disruption that technology creates.”