Traveling to six countries in eighteen days, I journeyed with the goal delving deeper into the roots of my family before World War II. As a child of refugees, my parents’ narrative is missing huge gaps of information. Still, more than seventy-eight years since the disappearance of my Grandmother and Uncles, we can only presume with a degree of certainty their demise in the mass graves of the forest outside of Riga, Latvia. In our data-rich world, archivists are finally piecing together new clues of history using unmanned systems to reopen cold cases.

The Nazis were masters in using technology to mechanize killing and erasing all evidence of their crime. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Treblinka, Poland. The death camp exterminated close to 900,000 Jews over a 15-month period before a revolt led to its dismantlement in 1943. Only a Holocaust memorial stands today on the site of the former gas chamber as a testimony to the memory of the victims. Recently, scientists have begun to unearth new forensic evidence of the Third Reich’s war crimes using LIDAR to expose the full extent of their death factory.

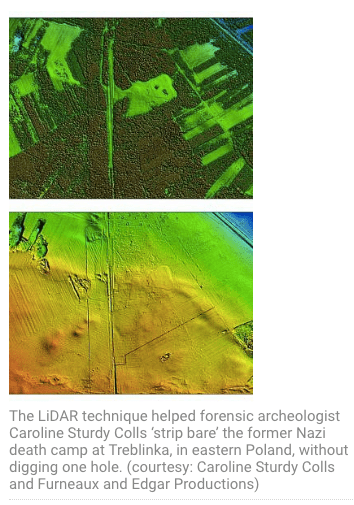

In her work, “Holocaust Archeologies: Approaches and Future Directions,” Dr. Caroline Sturdy Colls undertook an eight-year project to piece together archeological facts from survivor accounts using remote sensors that are more commonly associated with autonomous vehicles and robots than Holocaust studies. As she explains, “I saw working at Treblinka as a cold case…Where excavation is not permitted, desirable or wanted, [non-invasive] tools offer the possibility to record and examine topographies of atrocity in such a way that the disturbance of the ground is avoided.” Stitching together point cloud outputs from aerial LIDAR sensors, Professor Sturdy Colls stripped away the post-Holocaust vegetation to expose the camp’s original foundations, “revealing the bare earth of the former camp area.” As she writes, “One of the key advantages that LIDAR offers over other remote sensing technologies is its ability to propagate the signal emitted through vegetation such as trees. This means that it is possible to record features that are otherwise invisible or inaccessible using ground-based survey methods.”

Through her research, Sturdy Colls was able to locate several previously unmarked mass graves, transport infrastructure and camp-era buildings, including structures associated with the 1943 prisoner revolt. She credits the technology for her findings, “This is mainly due to developments in remote sensing technologies, geophysics, geographical information systems (GIS) and digital archeology, alongside a greater appreciation of systematic search strategies and landscape profiling,” The researcher stressed the importance of finding closure after seventy-five years, “I work with families in forensics work, and I can’t imagine what it’s like not to know what happened to your family members.” Sturdy Colls’ techniques are now being deployed across Europe at other concentration campsites and places of mass murder.

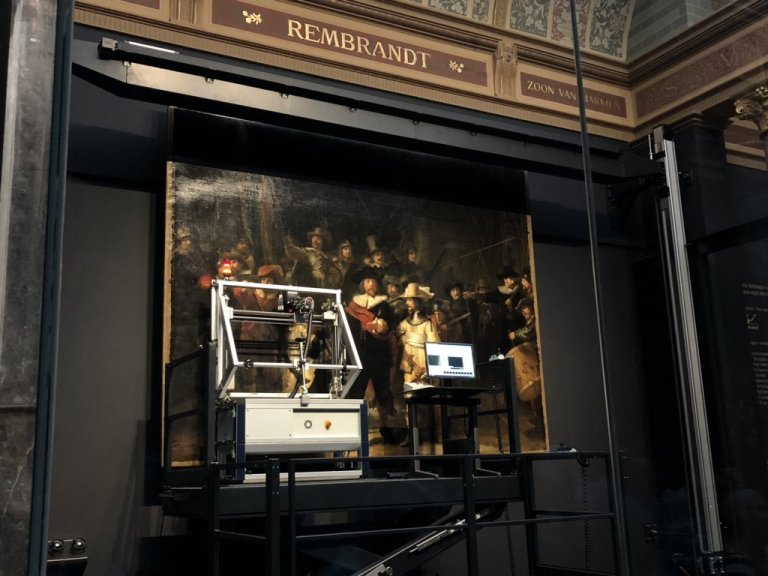

Flying north from Poland, I landed in the Netherlands city of Amsterdam to take part in their year-long celebration of Rembrandt (350 years since his passing). At the Rijksmuseum’s Hall of Honors, a robot is featured in front of the old master’s monumental work, “Night Watch.” The autonomous macro X-ray fluorescence scanner (Macro-XRF scanner) is busy analyzing the chemical makeup of the paint layers to map and database the age of the pigments. This project, aptly named “Operation Night Watch,” can be experienced live or online showcasing a suite of technologies to determine the best methodologies to return the 1642 painting back to its original glory. Night Watch has a long history of abuse including two world wars, multiple knifings, one acid attack, botched conservation attempts, and even the trimming of the canvas in 1715 to fit a smaller space. In fact, its modern name is really moniker of the dirt build up over the years, not the Master’s composition initially entitled: “Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq.”

In explaining the multi-million dollar undertaking the museum’s director, Taco Dibbits, boasted in a recent interview that Operation Night Watch will be the Rijksmuseum’s “biggest conservation and research project ever.” Currently, the Macro-XRF robot takes 24 hours to perform one scan of the entire picture, with a demanding schedule ahead of 56 more scans and 12,500 high-resolution images. The entire project is slated to be completed within a couple of years. Dibbits explains that the restoration will provide insights previously unknown about the painter and his magnum opus: “You will be able to see much more detail, and there will be areas of the painting that will be much easier to read. There are many mysteries of the painting that we might solve. We actually don’t know much about how Rembrandt painted it. With the last conservation, the techniques were limited to basically X-ray photos and now we have so many more tools. We will be able to look into the creative mind of one of the most brilliant artists in the world.”

Whether it is celebrating the narrative of great works of art or preserving the memory of the Holocaust, modern conservatism relies heavily on the accessibility of affordable mechatronic devices. Anna Lopuska, a conservator at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland, describes the Museum’s herculean task, “We are doing something against the initial idea of the Nazis who built this camp. They didn’t want it to last. We’re making it last.” New advances in optics and hardware, enables Lopuska’s team to catalog and maintain the massive camp site with “minimum intervention.” The magnitude of its preservation efforts is listed on its website, which includes: “155 buildings (including original camp blocks, barracks, and outbuildings), some 300 ruins and other vestiges of the camp—including the ruins of the four gas chambers and crematoria at the Auschwitz II-Birkenau site that are of particular historical significance—as well as more than 13 km. of fencing, 3,600 concrete fence posts, and many other installations.” This is on top of a collection of artifacts of human tragedy, as each item represents a person, such as “110 thousand shoes, about 3,800 suitcases, 12 thousand pots and pans, 40 kg. of eyeglasses, 470 prostheses, 570 items of camp clothing, as well as 4,500 works of art.” Every year more and more survivors pass away making Lopuska’s task, and the unmanned systems she employs, more critical. As the conservationist reminds us, “Within 20 years, there will be only these objects speaking for this place.”