Look, I get it, as with the wall or resurrecting the coal industry, Space Force probably seems like the newest hyperbole that’s bubbled up from our President’s imagination. If your base tosses you vote for it, why not see how far it goes, right? Should we get it all out? Queue star wars jokes; queue audience laughter—mutually affirm what a Drumpf Trump is.

All the same, a wise man somewhere has said there’s truth in what you hate. The reality is that power projection never ends. Just in the same way power has projected into naval and air forces, no amount of imploring or chiding from the UN or Neil de Grasse Tyson will stop it from bleeding into space. As the only non-authoritarian candidate grasping for this brass ring, we have to swallow an ounce of realpolitik or, all hyperbole aside, have Putin and Xi do it to us.

Space and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

There’s varying on why we want to be in space. Currently, scientific and corporate interests have the most mindshare in the public. The UN and Tyson are emphatic about the scientific boons. Silicon Valley has a vague interest in satellites or, further off, drawing raw commodities from asteroids. “It will be the greatest adventure ever”, Elon Musk frequently summarizes, attempting to weave in Space X’s big picture.

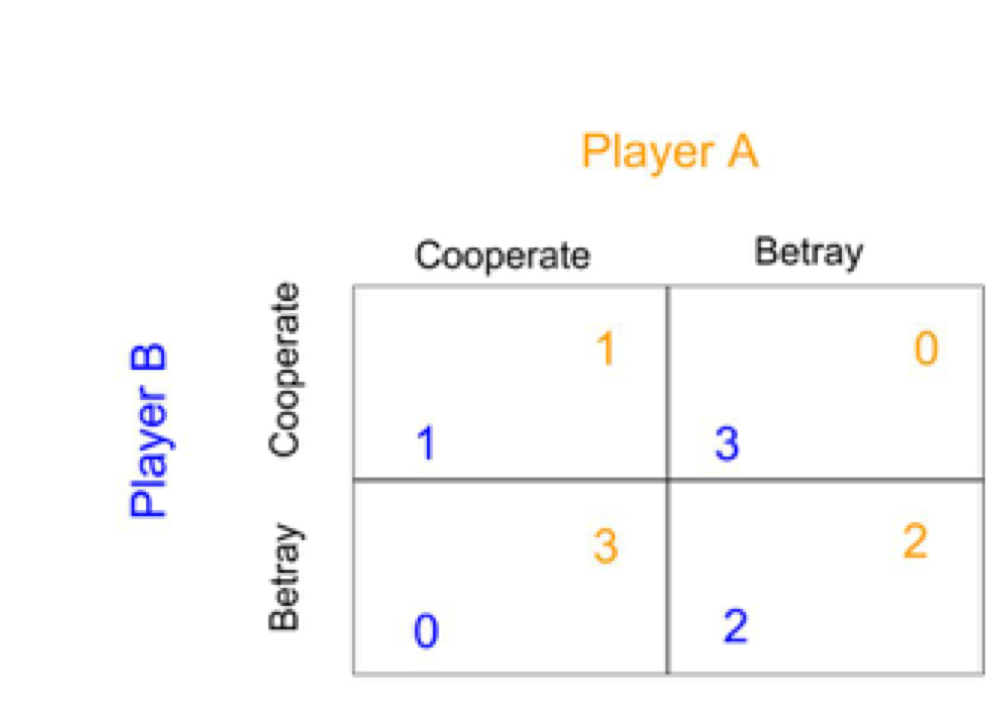

I think the best idea that drives Space’s urgency is the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Formulated by Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher at the RAND Institute, the Prisoner’s Dilemma concludes that particular circumstances make cooperation impossible. By analogy of convicts bargaining with lawyers, Flood and Dresher outlined the circumstances as:

- If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves two years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve one year in prison (on the lesser charge).

Put on a graph, the Prisoner’s Dilemma looks like this:

In political terms, the Prisoner’s Dilemma explains multiple historical paradoxes. Why the Cold War? How come the Germans had to sink the Lusitania and the Japanese Pearl Harbor? When the payoff for action and the stakes of inaction become too extreme, collaboration is impossible.

Obviously, there’s a danger to this logic. RAND conceived of the Prisoner’s Dilemma during the Cold War. The paranoid rationale it engenders of ‘if we don’t move first…’ and of preemptive strike quickly becomes a slippery slope. You can resume the draft and send more armies to Vietnam as you’d like, but eventually, some investments are sunk costs.

Space

Space easily pays off, though. Space isn’t only pelting asteroids inexpensively, but dominating the softer gradients of power also, allowing you to starve your enemies so that they can hear your terms of surrender.

The British Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan termed such subtle force as lines of communication. Lines of communication submit that, after a certain point, mobility and logistics pay off more than brute force. In his ‘19th Century Argument for Space Force’ for Wired Magazine, Nick Stockton makes the elegant analogy between naval power in the 19th century to space power in 21st. Naval power isn’t only warships, but also the agency to choke off enemy trade, rapidly transport armies, and act as the arteries for large empires. Fully leveraging this subtle power allowed Britain, among other reasons, to establish global Imperium in the 19th century.

Even with current technology, space power is even more subtle and potent than naval power. Principally, this is because of how dependent the digital economy is on satellites. This encompasses the internet, for example. Without the fixed satellite services, current bandwidth would have to be rerouted to the undersea and land cables that most engineers agree are too old, brittle, and would rupture from trying to handle it. Along with the fact that TV and cell phones would be directly cut down, a satellite attack would effectively blind entire populations to an enemy invasion.

GPS is also dependent on satellites. Besides navigation, multiple industries rely on GPS’ absolutely precise time stamps to synchronize extreme volumes of data. This obviously includes the financial sector, who’s live data streams and high-frequency trading are entirely premised on a fixed global clock. More significantly, this includes the energy sector, which needs GPS’ timestamps to synchronize energy transfers across the country. Functionally every facet of modern life is downstream of satellite technology.

Obviously, modern warfare also requires satellites. Like the internet, the military requires clear bandwidth to communicate with each other but, most importantly, GPS to coordinate troops and read enemy positioning. Satellites now function as both the eyes of modern war and the power socket of the modern economy. Poke them out—with the various anti-satellite weapons China and Russia have developed, for example—and you essentially send your enemy back to 20th-century methods.

On American Guilt

You’d think some degree of this would be intuitive, right? Trump, Star Trek/War jokes aside, you’d think the smirk would get tire before, eventually, people would grant that even if it’s impractical now, at some point entities will leverage space as the final dimension of war.

Apparently not. So far, Space Force coverage has mostly been listicles nitpicking some detail or other about why it just doesn’t add up. Take for example Loren Thompson’s ‘10 Ways a Space Force Will Make America Weaker’ which includes, among inspiring ways: “(#2) It will create new barriers to joint force integration” and “(#4) It will replicate abilities already resident elsewhere”.

I can imagine, too, that while thinking about the paradox, Prisoner A briefly consulted their own panel who asked similar questions. ‘How will prisoner B feel? Won’t there be a lot of paperwork if you testify? And what would you do with freedom, your record being what it is?’. For the prisoner’s own sake, I would hope that somebody else on the panel would nudge them that prisoner B is thinking is the same thing.

These listicles are less surprising because of their technical ignorance, however than by the hypocrisy of its supports. While Mr. Thompson has a respectable, consistent history picking through military budgets and new weaponry on Forbes, the audience most likely to share his articles simultaneously double think significantly more budget and bureaucratic heavy legislation. ‘Never Trump’ conservatives critiquing Space Force will at the same time advocate more expensive pushes into the Middle East, while liberals will platform Democratic Socialists like Ocasio-Cortez proposing $40 trillion welfare plans. Critique Space Force ethically, but don’t hide behind accounting if it’s not genuine.

The goofiness, I think, is symptomatic of a defect in the collective psychology. It’s my assertion that as Americans, we don’t feel entitled to even more authority, leverage, or potentially more territory gained in space. Trump, for many, isn’t merely an authoritarian wanting to send-people-back, but the newest incarnation in America’s tradition of hatred. Smallpox, slavery, internment, Vietnam, the failure of Iraq…this is all moral baggage we’re afraid of spreading anywhere, even if it’s desolate land like space.

Understanding our history and even being furious with it is essential. Doing so sets the standards for our future expectations and how our citizens will be educated to treat one another and serve our nation.

Still, it’s intellectually dishonest and politically sterilizing not to ground ourselves in context. I don’t mean the void term of historical context, but today’s very real modern landscape of tradeoffs and of other interests seeking hegemony: China and Russia.

If you’re liberal, these nations really should horrify you. This isn’t just because they shoot journalists, homosexuals, and rig elections, but because on the most existential, metaphysical level they reject cosmopolitanism. What would they do with space? Judging how they’ve seized much of Malaysia, the South Chinese Sea and Crimea, space would be for their own ethno-religiously defined flocks. These nations reject NATO’s goal of a frictionless landscape that best empowers individuals to trade, collaborate and express themselves irrespective of their pre-configured identities.

I don’t intend to render a cartoon of good vs. evil, but to elucidate the ethical stakes of this contest. While on Earth there’s nothing principally invalid about peaceful, tempered nationalistic identity (Israel, post-Yugoslavia, South Africa) space is the one opportunity we have to overcome these psychological crutches. Space shouldn’t be cordoned off with ethnic or religiously enforced borders, but blank for any cosmopolitan with talent and willpower to shape it.

Even if the original intentions were corrupt, America has committed to enforcing international order. After all the wars we’ve entered, it’s a type of mental masturbation to imagine how else we could’ve spent the lives and tax revenue on infrastructure, welfare programs or, yes, innocent space exploration. As a continental nation with essentially bottomless natural reserves, an entirely alternate history was possible wherein we followed Washington’s advice to leave the world alone.

Conversely, we’ve made the jump with the calculation that global events eventually catch up to us. In this shifting landscape of trade-offs, we decided that effort, lives, and capital spent towards killing totalitarianism pays off more than having smooth roads. To try on the most vulgar example: our conscience decided that we could never trade with or enrich a Europe intent on Aryan supremacy and that we want to snuff communism before the nation’s capital is exhausted. None of this is to mention the ethics of this decision, obviously.

We continue paying these tradeoffs today. Reading this post, I’m sure it’s not hyperbole to imagine a liberal reading this thinking ‘Why must space be American? Why not a more enlightened nation like Sweden, Germany or Canada?’

This person takes for granted that these liberal gems largely exist because of America’s protection. It’s because we foot Germany’s defense budget with our own troops—both with literal military bases in Germany and by dealing with ISIS for them—that they’re able to divert a relative abundance of capital into welfare programs. In order for these nations to go to space, they would have to accept the same economic and cultural tradeoffs as America, China, and Russia. In the meantime, we represent their interests in the race.

We have to accept that we are the current Romans or Victorians. We are the Empire the globe reacts to. While every Empire has its inevitable collapse, ours doesn’t seem to be imminent and everywhere we backtrack now becomes a vacuum.

Grieving our ancestors’ original sins, our apology to history can either be a withdrawal—mournful, sad, apparently wise—or to act preemptively like the force we wish we’d been and lay the foundation of a cosmos populated with more righteous people.