I’m a member of ffVC’s Acceleration Team focused on supporting our portfolio companies in financial budgeting and modeling. At our firm, we have a fundamental belief that companies should be run using a metric-based approach. Every quarter our investment team requests a series of pre-specified, idiosyncratic metrics from our portfolio companies. This could be as simple as Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Life Time Value (LTV) or something more company-specific, like Ratio of Paid Users to Total Users. It sounds simple, but I find tracking core metrics particularly important.

In this post, I’ll use a broad, hypothetical example of making revenue projections for an early-stage enterprise SaaS company to demonstrate the value of an anticipatory, data-driven projection approach.

One of the most exciting aspects of being an early-stage venture capital investor is predicting the future; that is, identifying forthcoming trends and weigh those against the potential of founders and their companies. Contemporaneously, projecting when, if, and how much these companies will create revenue is equally as challenging. While some may dismiss robust financial modeling at such an early stage, it’s an essential step in the infancy of a company.

After ffVC invests in a company, we offer them the support of our Acceleration Team. While these services range from accounting to product engineering, communications, and strategy, this post will emphasize the financial modeling aspect of how we work with our portfolio companies.

As is often the case, let’s assume that the revenue forecasts presented by the company during Due Diligence were based on its pipeline of future deals. The forecast took the number of deals in the pipeline, multiplied by the value of each deal, and then discounted this by a factor to reflect the stage the deal was in and its relative likelihood of success. In short, the projections were static; revenue only factored in identified deals in the pipeline.

While this is a reasonable approach to revenue projections, it becomes very hard to quantitatively answer questions that will arise, such as, “What would happen if you hired three more salespeople?” To answer this question, you need dynamic forecasts.

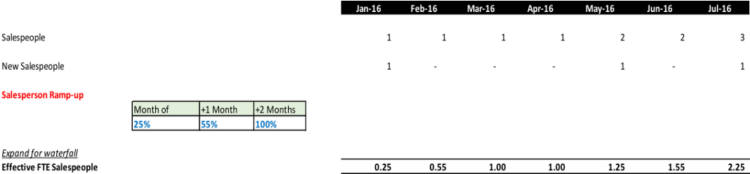

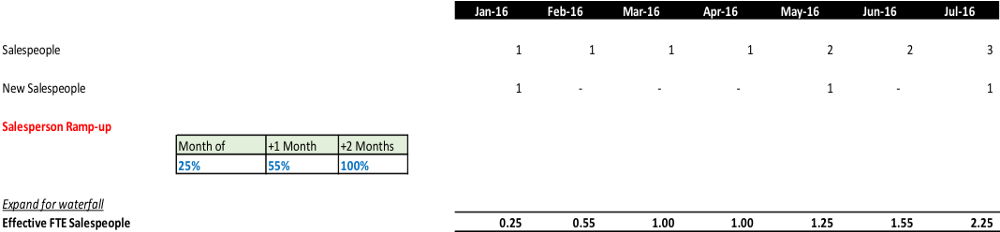

The reason it’s important to be able to quantify the effect of additional salespeople is that when selling enterprise software, salespeople are the fundamental drivers of revenue. See below Item 1, which highlights the beginning of our dynamic revenue forecasts.

As you can see, the revenue build starts with the number of salespeople in the company. Next, we model out the benefit of adding additional salespeople.

An important consideration is the ramp-up rate of a salesperson. The revenue salespeople generate is built off an annual sales quota. As such, it’s unreasonable to assume that salespeople are as effective in their first month on the job as they are in their second or third month. Consequently, it’s important to build in a salesperson ramp-up when modeling the effect of a new salesperson.

In this case, we have assumed that in the first month a new salesperson is brought on, they are 25% effective, in the next month they are 55% effective, and then finally in the third month (+2 months) and in every consecutive month thereafter, they are 100% effective.

If the number of salespeople in a company is viewed as the fundamental driver of revenue, the ramp-up rate of new salespeople should be viewed as one of the first influences on revenue.

If we were to change the assumption to 50% effectiveness in their first month and then 100% effectiveness from then on, we would be decreasing the ramp-up and creating more aggressive revenue forecasts. This influence on revenue can be viewed as the first of a number of quantifiable metrics that is incorporated into this revenue build.

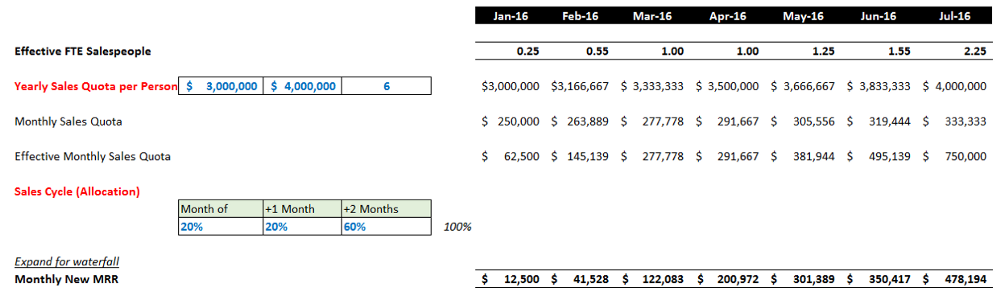

Next, let’s look at Item 2.

Another assumption that helps shape revenue projections is the sales cycle. This is particularly relevant with enterprise SaaS companies, where the contract value can be hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. In large deals, it’s common to take a number of months to close a deal, and this should be reflected in the model.

In contrast with the salesperson ramp-up, which increases to 100% over time, the sales cycle assumption should allocate potential revenue over future periods. As a result, the assumptions should sum to 100%.

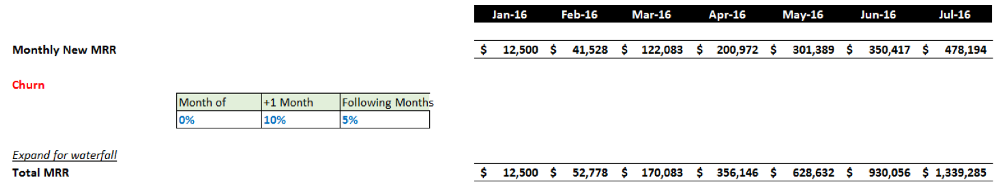

The final item I’ll explore is Item 3.

A very important consideration when projecting SaaS revenue is churn. Your customer churn rate is inversely related to your retention rate, which also makes it inversely related to your ability to sustainably grow revenue.

Conclusion

The hypothetical dynamic revenue build I’ve outlined here is an intentionally overly simplistic example so as not to lose focus from the contention of the post.

A more in-depth revenue build should include, at a minimum, the monthly revenue per SaaS contract, which would allow you to also project SaaS customers as well as growth in the per contract revenue over time. Growth in the contract revenue over time could be thought of as another influence on revenue.

Let’s reflect on what we have done here. At a minimum, this process has forced the management team of the company to think about the operations of their business in a holistic manner. The process connects the dots between the operations of the business and its financial success.

It may well be the case that the projected revenue achieved under this method is very similar to that projected by the company during its Due Diligence phase. However, this isn’t the fundamental value-add of financial modeling for early stage companies. What we have achieved here is the identification of a number of factors that influence this company’s revenue.

Whereas during Due Diligence your revenue depends on what you already know (deals in the pipeline), this dynamic approach allows you to truly speculate about where your business could go.

Assuming you build a more complicated revenue model than above, you’d theoretically have sight into every key metric that will allow your business to succeed from a revenue standpoint and have clarity on the metrics you should be tracking.

These are all measurable metrics, and what’s more, with the dynamic nature of the assumptions in this model, we can quantifiably see the impact of improvements or deterioration in each metric. If an investor asks you what the impact of hiring another three salespeople is, you can tell them instantly.

At ffVC, we consider ourselves active investors and offer hands-on support to help our founders succeed. Consequently, the reason we mandate that our portfolio companies share their KPIs with us every quarter is so that we can help where help is needed. With a portfolio of 90+ companies all tracking a mixture of general and idiosyncratic metrics, we have great insight into what successful metrics look like at all stages of a business. The role of a passive investor is to contribute capital and watch you grow; the role of an active investor is to contribute capital and help you grow.