The internet hummed last week with reports that “Humans Still Make Better Surgeons Than Robots.” Stanford University Medical Center set off the tweetstorm with its seemingly scathing report on robotic surgery. When reading the research of 24,000 patients with kidney cancer, I concluded that the problem lied with the humans overcharging patients versus any technology flaw. In fact, the study praised robotic surgery for complicated procedures and suggested the fault lied with hospitals unnecessarily pushing robotic surgery for simple operations over conventional methods, which led to “increases in operating times and cost.”

Dr. Benjamin Chung, the author of the report, stated that the expenses were due to either “the time needed for robotic operating room setup” or the surgeon’s “learning curve” with the new technology. Chung defended the use of robotic surgery by claiming that “surgical robots are helpful because they offer more dexterity than traditional laparoscopic instrumentation and use a three-dimensional, high-resolution camera to visualize and magnify the operating field. Some procedures, such as the removal of the prostate or the removal of just a portion of the kidney, require a high degree of delicate maneuvering and extensive internal suturing that render the robot’s assistance invaluable.”

Chung’s concern was due to the dramatic increase in hospitals selling robotic-assisted surgeries to patients rather than more traditional methods for kidney removals. “Although the laparoscopic procedure has been standard care for a radical nephrectomy for many years, we saw an increase in the use of robotic-assisted approaches, and by 2015 these had surpassed the number of conventional laparoscopic procedures,” explains Chung. “We found that, although there was no statistical difference in outcome or length of hospital stay, the robotic-assisted surgeries cost more and had a higher probability of prolonged operative time.”

The dexterity and precision of robotic instruments has been proven in live operating theaters for years, as well as multitude concept videos on the internet of fruit being autonomously stitched up. Dr. Joan Savall, also of Stanford, developed a robotic system that is even capable of performing (unmanned) brain surgery on a live fly. For years, medical students have been ripping the heads off of the drosophila with tweezers in the hopes of learning more about the insect’s anatomy. Instead, Savall’s machine gently follows the fly using computer vision to precisely target its thorax; literally a moving bullseye the size of a period. The robot is so careful that the insect is unfazed and flies off after the procedure. Clearly, the robot is quicker and more exacting than even the most careful surgeon. According to journal Nature Methods, the system can operate on 100 flies an hour.

Last week, Dr. Dennis Fowler of Columbia University and CEO of Platform Imaging, said that he imagines a future whereby the surgeon will program the robot to finish the procedure and stitch up the patient. He said senior surgeons already pass such mundane tasks to their medical students, ‘so why not a robot?’ Platform Imaging is an innovative startup that aims to reduce the amount of personnel or equipment a hospital needs when performing laparoscopic surgeries. Long-term, it plans to add snake robots to its flexible camera to empower surgeons with the greatest amount of maneuverability. In addition to the obvious health benefits to the patient, robotic surgeries like Dr. Fowler’s will reduce the number of workplace injuries to laparoscopic surgeons. According to a University of Maryland study, 87% of surgeons who perform laparoscopic procedures complain of eye strain, hand, neck, back and leg pain, headaches, finger calluses, disc problems, shoulder muscle spasm and carpel tunnel syndrome. Many times these injuries are so debilitating that they lead to early retirement. The author of the report, Dr. Adrian Park, explains “In laparoscopic surgery, we are very limited in our degrees of movement, but in open surgery we have a big incision, we put our hands in, we’re directly connected with the target anatomy. With laparoscopic surgery, we operate by looking at a video screen, often keeping our neck and posture in an awkward position for hours. Also, we’re standing for extended periods of time with our shoulders up and our arms out, holding and maneuvering long instruments through tiny, fixed ports.” In Dr. Fowler’s view, robotic surgery is a game changer by expanding the longevity of a physician’s career.

At the children’s National Health System in Washington, D.C, the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) provided a sneak peak to the future of surgery. Using advanced 3D imaging systems precise force-sensing instruments the STAR was able to autonomously stitch up soft tissue samples (of a living pig above) with sub-millimeter accuracy that is by far greater than even the most precise human surgeons. According to the study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, there are 45 million soft tissue surgeries performed each year in the United States.

Dr. Peter Kim, STAR’s creator, says “Imagine that you need a surgery, or your loved one needs a surgery. Wouldn’t it be critical to have the best surgeon and the best surgical techniques available?” Dr. Kim espouses, “Even though we take pride in our craft of doing surgical procedures, to have a machine or tool that works with us in ensuring better outcome safety and reducing complications—[there] would be a tremendous benefit.”

“Now driverless cars are coming into our lives,” explains Dr. Kim. “It started with self-parking, then a technology that tells you not to go into the wrong lane. Soon you have a car that can drive by itself.” Similarly, Dr. Kim and Dr. Fowler envision a time in the near future when surgical robots could go from assisting humans to being overseen by humans. Eventually, Dr. Kim says they may one day take over. After all, Dr Kim’s “programmed the best surgeon’s techniques, based on consensus and physics, into the machine.”

The idea of full autonomy in the operating room and on the road raises a litany of ethical concerns, such as the acceptable failure rate of machines. The value proposition for self-driving cars is very clear – road safety. In 2015, there were approximately 35,000 road fatalities; self-driving cars will reduce that figure dramatically. However, what is unclear is what will be the new acceptable rate of fatalities with machines. Professor Amnon Shashua, of Hebrew University and founder of Mobileye, has struggled with this dilemma for years. “If you drop 35,000 fatalities down to 10,000 – even though from a rational point of view it sounds like a good thing, society will not live with that many people killed by a computer,” explains Dr. Shashua. While everyone would agree that zero failure is the most desired, outcome in reality Shashua says, “this will never happen.” He elaborates, “What you need to show is that the probability of an accident drops by two to three orders of magnitude. If you drop [35,000 fatalities] down to 200, and those 200 are because of computer errors, then society will accept these robotic cars.”

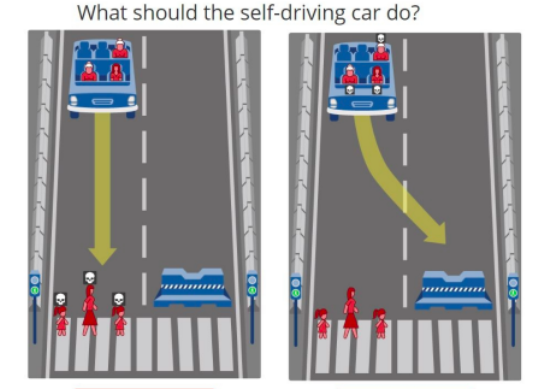

Dr. Iyad Rahwan of MIT is much more to the point, “If we cannot engender trust in the new system, we risk the entire autonomous vehicle enterprise.” According to his research, “Most people want to live in a world where cars will minimize casualties. But everybody wants their own car to protect them at all costs.” Dr. Rahwan is referring to the Old Trolly Problem – does the machine save its driver or the pedestrian when encountered with a choice? Dr. Rahwan declares, “This is a big social dilemma. Who will buy a car that is programmed to kill them in some instances? Who will insure such a car?” Last May at the Paris Motor Show Christoph von Hugo, of Daimler Benz, emphatically answered: “If you know you can save at least one person, at least save that one. Save the one in the car.”