This past week, a robotic first happened: ABB’s Yumi robot conducted the Lucca Philharmonic Orchestra in Pisa, Italy. The dual-armed robot overshadowed even his vocal collaborator, Italian tenor Andrea Bocelli. While many will try to hype the performance as ushering in a new new era of mechanical musicians, Yumi’s artistic career was short-lived as it was part of the opening ceremonies of Italy’s First International Festival of Robotics.

Italian conductor Andrea Colombini said of his student, “The gestural nuances of a conductor have been fully reproduced at a level that was previously unthinkable to me. This is an incredible step forward, given the rigidity of gestures by previous robots. I imagine the robot could serve as an aid, perhaps to execute, in the absence of a conductor, the first rehearsal, before the director steps in to make the adjustments that result in the material and artistic interpretation of a work of music.”

Yumi is not the first computer artist. In 1973, professor and artist, Harold Cohen created a software program called AARON – a mechanical painter. AARON’s works have been exhibited worldwide, including at the prestigious Venetian Biennale. Following Cohen’s lead, Dr Simon Colton of London’s Imperial College created “The Painting Fool,” with works on display in Paris’ prestigious Galerie Oberkampf in 2013. Colton wanted to test if he could cross the emotional threshold with an artistic Turning Test. Colton explained, “I realized that the Painting Fool was a very good mechanism for testing out all sorts of theories, such as what it means for software to be creative. The aim of the project is for the software itself to be taken seriously as a creative artist in its own right, one day.”

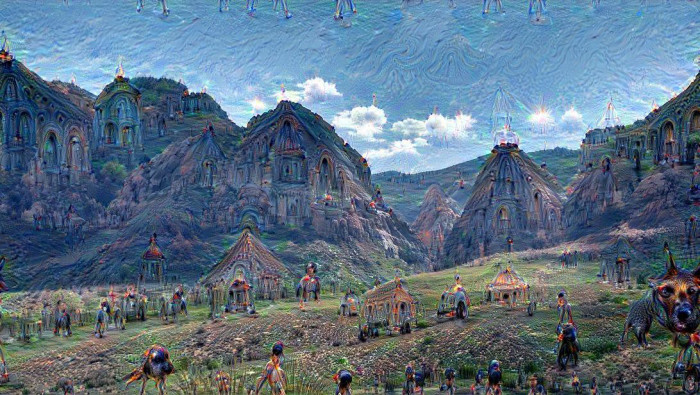

In June 2015, Google’s Brain AI research team took artistic theory to the next level by infusing its software with the ability to create a remarkably human-like quality of imagination. To do this, Google’s programmers took a cue from one of the most famous masters of all time, Leonardo da Vinci. Da Vinci suggested that aspiring artists should start by looking at stains or marks on walls to create visual fantasies. Google’s neural net did just that, translating the layers of the image into spots and blotches with new stylized painterly features (see examples below).

1) Google uploaded a photograph of a standard Southwestern scene:

2) The computer then translated the layers as below:

In describing his creation, Google Brain senior scientist Douglas Eck said this past March, “I don’t think that machines themselves just making art for art’s sake is as interesting as you might think. The question to ask is, can machines help us make a new kind of art?” The goal of Eck platform called Magenta is to enable laypeople (without talent) to design new kinds of music and art, similar to synthetic keyboards, drums and camera filters. Dr. Eck himself is an admittedly frustrated failed musician who hopes that Magenta will revolutionize the arts in the same way as the electric guitar. “The fun is in finding new ways to break it and extend it,” Eck said excitedly.

The artistic development and growth of these computer programs is remarkable. Cohen, who passed away last year, said in a 2010 lecture regarding AARON “with no further input from me, it can generate unlimited numbers of images, it’s a much better colorist than I ever was myself, and it typically does it all while I’m tucked up in bed.” Feeling proud, he later corrected himself, “Well, of course, I wrote the program. It isn’t quite right to say that the program simply follows the rules I gave it. The program is the rules.”

In reflecting on the societal implications of creative bots, one can not help to be reminded of the famous statement by philosopher René Decartes: “I think, therefore I am.” Challenging this idea for the robotic age, Professor Arai Noriko tested the thinking capabilities of robots. Noriko led a research team in 2011 at Japan’s National Institute of Informatics to build an artificial intelligence program smart enough to pass the rigorous entrance exam of the University of Tokyo.

“Passing the exam is not really an important research issue, but setting a concrete goal is useful. We can compare the current state-of-the-art AI technology with 18-year-old students,” explained Dr. Noriko. The original goal set out by Noriko’steam was for the Todai robot (named for the University) to be admitted to college by 2021. At a Ted conference earlier this year, Noriko shocked the audience by revealing the news that Todai beat 80% of the students taking the exam, which consisted of seven sections, including math, English, science, and even a 600-word essay. Rather than celebrating, Noriko shared with the crowd her fear,”I was alarmed.”

Todai is able to search and process an immense amount of data, but unlike humans it does not read, even with 15 billion sentences already in its neural network. Noriko reminds us that “humans excel at pattern recognition, creative projects, and problem solving. We can read and understand.” However, she is deeply concerned that modern educational systems are more focused on facts and figures than creative reasoning, especially because humans could never compete with the fact-checking of an AI. Noriko pointed to the entrance exam as an example, the Todai robot failed to grasp a multiple choice question that would have been obvious even to young children. She tested her thesis at a local middle school, and was dumfounded when one-third of students couldn’t even “answer a simple reading comprehension question.” She concluded that in order for humans to compete with robots, “We have to think about a new type of education. ”

Cohen also wrestled with the question of a thinking robot and whether his computer program could ever have the emotional impact of a human artist like Monet or Picasso. In his words, to reach that kind of level a machine would have to “develop a sense of self.” Cohen professed that “if it doesn’t, it means that machines will never be creative in the same sense that humans are creative.” Cohen later qualified his remarks about robotic creativity, adding, “it doesn’t mean that machines have no part to play with respect to creativity.”

Noriko is much more to the point, “How we humans will coexist with AI is something we have to think about carefully, based on solid evidence. At the same time, we have to think in a hurry because time is running out.” John Cryan, CEO of Deutsche Bank, echoed Noriko’s sentiment at a banking conference last week. Cryan said “In our banks we have people behaving like robots doing mechanical things, tomorrow we’re going to have robots behaving like people. We have to find new ways of employing people and maybe people need to find new ways of spending their time.”