The key to the future of consumer financial services is data…but not in the way most industry veterans think.

New technology is allowing companies to capture more data about customers and their transactions than ever before. As an industry, we are starting to put that data to use in smarter products and more data-driven processes. Bank of America, for example, tracks customers across multiple channel interactions, using the combination of website clicks, transaction records, banker notes, and call center records to build a full picture of “customer journeys.” The bank uses this data to make proactive offers to customers including credit card or mortgage refinancing, or cash-back deals to holders of credit and debit cards based on spending patterns. In insurance, Progressive offers Snapshot, a program where drivers earn discounts on car insurance by giving access to detailed vehicle driving data, which is being used to build better actuarial models. OnDeck Capital uses bank transaction data of small business to make better decisions about which small business are less likely to default on loans.

It is tempting to think that the most important question about data is, “How do we best use this data?” However, an even more pressing question–and one that underpins a major battle brewing in financial services–is, “Who owns the data?” When a customer uses a credit card, who owns that information on what they purchased, where, and for how much? What rights do consumers have to access that data, to restrict access, to decide who can use it and how, or even to remove it?

Data ownership has been a contentious issue for consumer internet giants such as Google and Facebook for years. Google and Facebook have sparred with the European Union over data privacy and “right to be forgotten” rules, culminating in 2014 in the Costeja case, where the Court of Justice of the EU ruled internet companies must consider requests from users to remove data about individuals from company servers. Both companies suffered a more recent blow from the invalidation of the data processing Safe Harbor by the Court of Justice–restricting internet companies‘ ability to export data collected on EU citizens to the United States for processing and analysis.

It is no surprise then that as finance enters the digital era, the issue of data ownership is beginning to appear on the corporate agenda. Financial institutions face a slightly different challenge compared to consumer internet companies. Whether due to a lack of advertising driven business models, longstanding perception as a safe place to store valuable assets, or significant oversight from industry regulators, consumers have been less vocal over concerns about financial institutions storing data about them. Consumers’ main concern with data stored by financial institutions is how easily can they access that data—and connect it to the financial app of their choice such as Mint, a personal financial management app, or Quickbooks, a small business accounting solution. While financial institutions seem to avoid some of the data-ownership headaches that Google and Facebook are dealing with they have an entirely different—and potentially scarier problem: consumers are opting for external products over in-house software.

The Utility Matrix

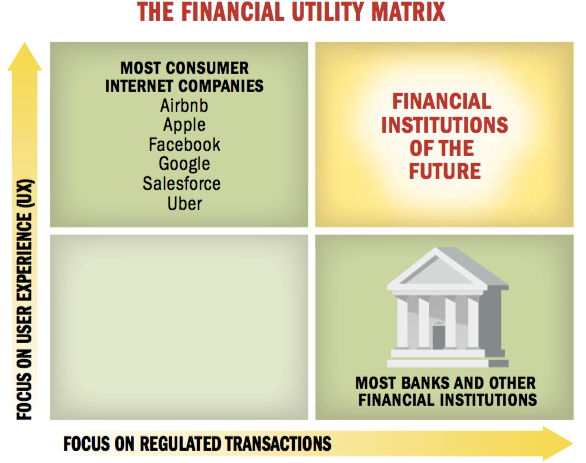

To understand why financial institutions are opting for non-bank solutions, lets consider something called the “Utility Matrix”—a rough plot of how focused a company is on optimizing for regulated transactions versus how focused it is on optimizing for User Experience (UX).

Most financial institutions are in the lower right quadrant: highly focused on efficient and compliant transactions, while lagging behind on customer UX. On the other hand, most consumer internet companies are in the upper left quadrant: highly focused on UX, while lagging behind on compliant transactional efficiency.

The key word here is “compliant”, since many technology companies often attempt to gain efficiencies by introducing a new business model with uncertain regulatory compliance. The emergence of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending (and eventual evolution into marketplace lending) is a prime example. Lending Club and Prosper both created innovative loan origination and funding models that – while highly efficient from a cost perspective – proved to be non-compliant with securities laws until forced to register as securities dealers. Similarly, in equity crowdfunding, sites launched sizeable businesses allowing consumers to invest in private companies that tread closely to an equity securities transaction. In 2011, an early crowdfunding pioneer, ProFounder, shut down in face of mounting pressure from the SEC, who claimed the site was engaging in general solicitor and must therefore register as a broker-dealer. The passage of the Jobs Act has created a new category of securities regulation for equity crowdfunding portals, but still leaves many restrictions in place.

Although many startups employ the “move fast, break things” strategy and rely on being too small to attract regulators’ attention, it is impossible to avoid forever. Once startups attract the eye of a local, state, or federal regulator, they have only one choice: comply or else receive a cease and desist order from a judge that cares little for how disruptive their innovation is. As painful as it is to adhere to regulation, it eventually becomes a requirement for a growing startup; they must either bring the skillset and knowledge in house or partner with an industry veteran with established people and processes. Learning to maneuver within an increasingly complex regulatory system is often an under-appreciated advantage that banks hold over their younger, more nimble competitors.

The Consumer Hack

On the whole, consumers can be rather demanding. They seek out the best experience at the lowest price, and when the market fails to provide the product they want, they find ways to stitch together multiple products to give themselves the best “solution”. In the innovation world, this is called a “consumer hack”, and it typically means there is a gap in the market.

Right now consumers are trying to optimize their situation by cherry-picking the secure, regulated transaction capabilities of banks and the slick, user-friendly UX of consumer internet companies. Essentially, consumers are saying, “Banks, you focus on providing fast and secure transactions, and internet companies, you focus on giving me a good user experience.”

In order to make this marriage work, consumers are starting to make use of data integrations between banks and internet companies through the use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

The issue now is the market has grown substantially – there are many more applications than just Quickbooks and Mint looking to access data and the banks are not thrilled. There are literally thousands of financial apps (and more created every day) that utilize transactional data from banks. The accounting, budgeting, lending, investing, and financial planning app verticals are increasingly crowded. These apps control the front-end customer experience while allowing consumers to conduct financial transactions by leveraging a financial institution’s back-end via API. But, in order to function or to provide any value to users, these apps require customer data from the financial institution.

In “hacking” together these sorts of financial interactions, consumers are drawing a line between companies that offer the user experience they want, and companies that offer the transaction capabilities they need. This poses a strategic quandary for financial institutions, as they must decide whether or not to provide easy, low-cost access to customer data and risk pushing themselves further into a transactional role with little to no control over the customer experience. Becoming a transactional utility with commodity products makes a bank easily replaceable and limits product cross-sell, the lifeblood of bank profitability. On the other hand, if banks restrict data access, they risk losing customers to other institutions that are more willing to collaborate with consumers’ preferred applications via API.

The Ownership Debate

At the heart of this debate is the question raised at the beginning of this article: “Who owns the data?” Banks argue that it is proprietary data that the bank generates as it goes about the business of serving its customers and therefore belongs to the bank. Internet companies argue that data should be a shared asset, and banks should allow startups to put the data to work, to provide new and innovative user experiences. At the center of this battle, consumers argue that they should have rights to control and remove their own personal data from bank systems if and when they want – preferably for free.

The earlier mentioned Costeja and Safe Harbor rulings by EU Couth of Justice show how this debate can go from being a public relations nuisance to a real cost center. In both cases what was once a strategic asset has been turned into a liability. Companies such as Facebook and Google must expend time and resources serving requests from individuals about their data, and must restructure their internal data storage and utilization processes to adhere to geographic boundaries (a confusing concept in the digital realm). In a few pen strokes, customer data was transformed from a company asset to a regulated material along the lines of alcohol, tobacco, and pharmaceuticals.

Although all sides of this debate hold merit, the argument may be moot in the end, unless you hold a Google or Facebook level monopoly within a category. Once you’re engaging a consumer in a debate over something as complicated as data ownership, you’re already delivering a sub-optimal user experience.

The Showdown

A showdown is brewing between banks and consumers over who does (or should) own the data and control its access. JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America have all recently captured headlines after throttling access to customer information by popular financial aggregator sites such as Mint and Quicken. Banks cite security, privacy and digital traffic congestion as concerns that influence their decisions, however this seems to have had little impact on consumers desire to get the best user experience available.

In a perfectly academic world (and likely most Silicon Valley blogs), a likely scenario in the data ownership debate between banks, internet companies, and customers is as follows:

- Most banks will opt to go for the upper right quadrant, rather than be marginalized as a transaction utility.

- A few banks will opt for the upper left and provide ultra low-cost transaction services with open data.

- Consumer internet companies will provide superior UX and partner with the low-cost transaction banks to provide the best solution.

- The majority of banks that compete for the upper right will go out of business.

We are already seeing the emergence of financial institutions that have chosen to focus on low cost back-end services rather than engaging directly with end customers. The Bancorp offers private white label deposit account products for non-bank partners, WebBank acts as the regulated loan originator for marketplace lenders such as LendingClub and Prosper, WealthForge provides a “Broker-Dealer As a Service” through an API for apps that deal in securities transactions, and Tradier provides a low-cost retail equity trading account that can only be accessed by connecting its API to an external app partner.

The wildcard variable in this situation is the presence of regulation and legal liability. Regulators tend to disapprove when transactions are divorced from customer interactions, and doing so opens financial institutions to significant legal liability. As a result of generations of loopholing to avoid regulation, deeming whether regulation applies to a particular company is often driven by how and from whom a given company is compensated. Often the only way to avoid regulation is to limit the ways in which a company can receive compensation, making it difficult to build a sustainable business model. For example, startups in the increasingly crowded personal investing app space are still struggling to discover monetization models that are connected with per-trade fees or compensation for trading ideas that do cause that startup to fall under the SEC guidelines for Introducing Brokers or Investment Advisors.

These complications will make it almost impossible for the academic scenario outlined above to play out; instead, we will see a much more closely matched battle than most industry participants realize.

Consumer internet companies have younger, less complicated, and more risk-taking corporate cultures than financial institutions, and they are obsessed with optimizing user experience, utilizing rapid prototyping processes, and leveraging low-cost digital marketing channels. This enables internet companies to innovate and implement new products where traditional institutions may fall behind. They also hold the advantages of having more data-driven processes and less scrutiny from regulators (at least initially).

At first glance it may appear that consumer internet companies have financial institutions outgunned. However, financial institutions have deep experience in security, legal, and regulatory management – three strengths critical for delivering financial services at scale. Banks have significantly stronger compliance processes and are much more adept at navigating the quasi-political nature of financial regulation. Startups may be optimized to create new products that consumers want to exist, but financial institutions are optimized to create new products that regulators want to exist. In this sense the two sides are evenly matched.

The Strategy

No matter the direction institutions decide to take, the showdown will continue to escalate. Institutions need to put a coordinated plan in place to address increasing requests from customers and partners to open data assets. Failure to do so will result in uncoordinated responses across business lines, which at best will result in pockets of negative publicity and lost revenue opportunity, and at worst will create an alienated customer base. To prepare, banks need to create a customer data strategy that supports their long-term business strategy, which will entail a series of steps:

- Inventory current capabilities

Financial institutions need to truly understand where their customers see them on the Utility Matrix– how do customers feel about the user experience provided in the bank’s products? Are they using the institution’s APIs with other external apps? Which apps, and why? Which apps do their competitor’s customers use?

Although it is tempting to answer these questions using internal data or customer surveys such as the infamous Net Promoter Score, this will not provide the necessary answers. Banks will need to conduct in-depth customer research to understand emerging qualitative behaviors. By understanding where consumers see them on the Utility Matrix, banks will gain an understanding of how susceptible they are to falling into the transaction role.

- Choose a battlefield

Once an institution has a view of its current capabilities, it can start to understand whether it can reasonably compete in the upper right quadrant. Does the bank have a strong product development process and delightful user experience? If so, the main focus should be to continue to incorporate processes that have become standard in the consumer internet space: rapid product development and testing, better use of digital marketing, smarter data-driven customer experiences.

If the bank is lagging significantly in delivering a competitive user experience, it is important to face the question of whether the institution can realistically compete in a digital world. This may require refocusing on either a transactional utility role, or on segments such as High Net Worth and Corporate users, where user experience may be outweighed by other factors such as relationship management, balance sheet availability, and price.

- Segment data assets

Once the institution has chosen its battlefield, it must survey its resources. In a digital world, data becomes the most precious resource. Institutions must segment all of the data assets available to them across both customer segments and products (e.g. mortgages vs. deposit accounts, consumer vs. small business). As part of this, institutions should also identify their own weaknesses and what legacy system problems prevent easy access to each data asset. They should also understand the varying levels of security and regulatory drivers that impact the ability to make data easily available.

- Establish a data strategy

With a chosen battlefield and an understanding of available resources, financial institutions must create a comprehensive data strategy that answers several key questions:

- Can customers access their data through an API?

- What are the costs associated with providing this access?

- How is customer data priced – free, freemium, or premium?

- Are there limits on how data can be used (e.g. only certain strategic partner apps)?

- How will the bank monitor and discover emerging data behaviors by customers?

- What is the bank’s legal and regulatory vulnerability to external data access?

- How secure are the institution’s data assets and access to them?

- Where should the bank focus its data integration and development efforts?

The Conclusion

When dust from the data ownership battle settles, (new) financial institutions will prevail over a system of bank utilities and consumer internet companies offering integrated “solutions”. The big question is whether the new digital financial institutions will have evolved from today’s consumer internet companies that learned to behave more like banks of today, or from banks that learned to become more like consumer internet companies.