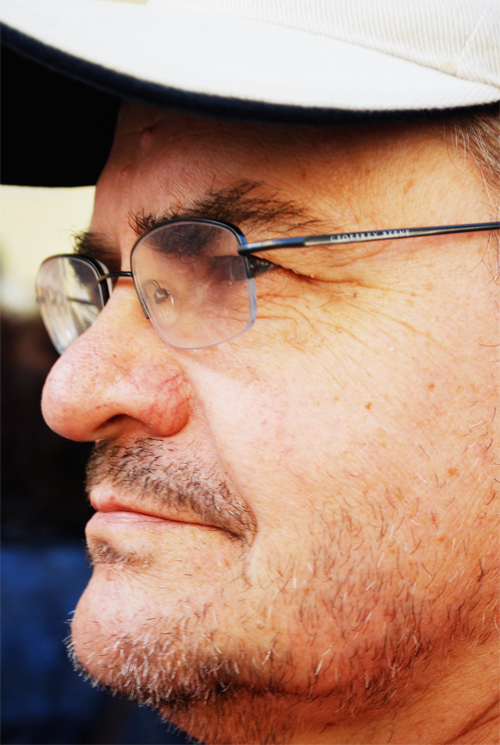

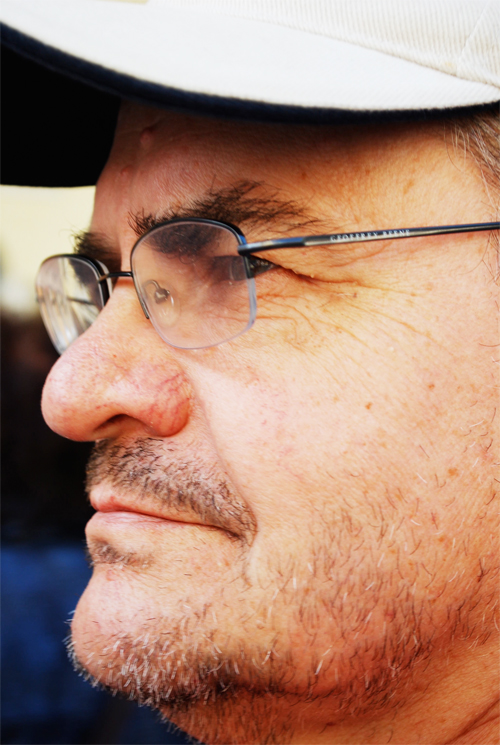

Sadly, John Ason passed away in 2019. This interview serves as a testament to the type of champion for entrepreneurship he was.

Welcome back to Inside the Mind of a NYC Angel Investor, a new series at AlleyWatch in which we speak with New York City-based Angel Investors. In the hot seat this time is John Ason, who has been investing in startups for over 20 years and serves as a mentor at Astia, Springboard, 37 Angels, The Vinetta Project, ERA, DreamIt, and TechLaunch. John spent the early part of his career at AT&T Bell Laboratories and today sees over 4,000 pitches per year as a professional angel investor. John sat down with AlleyWatch to talk about managing risk as an angel investor, the types of angels that make the biggest mistakes, and his belief that industry experience is overrated.

If you are a NYC-based Angel interested in participating in this series, please send us an email. We’d love to chat. If you are interested in sponsoring this series that showcases the leading minds in angel investing in NYC, we’d also love to chat. Send us a note.

Bart Clareman, AlleyWatch: Tell us about your journey into investing in startup ventures?

John Ason: I spent a career at Bell Laboratories with AT&T always doing technology work. During the last 15 years I was doing marketing and selling of large software systems to telecommunications companies overseas, primarily the Far East.

I made money in the public markets, and retired for about a year. I goofed off, played around, and got bored, so I then got into angel investing.

It was not a cultural shock in any way because I was doing bleeding edge technology at Bell Laboratories, so everything was the same other than that startups had no shipping department or legal department so you had to do everything.

Bell Labs is talked about as one of the forefathers to the New York tech scene – what was it like to work there, and why was it so foundational to the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem here?

At Bell Labs if you wanted to you could do bleeding edge work. You could always get work that was very different, very new. That was one big impetus.

Second, the research group had some of the sharpest, smartest people around. A lot of friends of mine were from the deep research area.

We also experienced the transition from being a purely US company to an international company, and I grew as part of that transition, I did a good 15 years internationally, primarily Japan and the Far East.

Also I had the opportunity to do a lot of projects like the AT&T Internet, the AT&T Cloud, which were way ahead of its time. The infrastructure, the software, the virtualizations were not available at the time, so these were nonfunctional to a large degree. Nevertheless, it gave me a very good background in those products and a glimpse into the future. Also, I loved having such a variety as opposed to working for a company where you were just programming COBOL or something for 30 years.

On your website you define yourself as an Early Seed State Angel, which you further define as an Angel that “invests in companies that have an idea, 1 or 2 founders, no revenues, no completed product and no history of success.” Why do you prefer early stage to later stage angel investing?

One reason is it’s exciting, and you’re learning new things. The second reason is, my research indicated that the return per dollar invested is highest at the early seed stage, then it drops off, then it comes back to a rational number in the public markets. So I felt I could get the best returns if I could manage the risks. My whole focus was on managing risk.

How do you manage risk with early stage companies, which, as you say, may have little more than a founder or two and an idea?

I don’t overpay for companies. I have a rigid formula that for the complete round the founder has to give up 20-30% equity. 90% of all startups fit into that range anyway, so I made it a rule. Under 20% it’s not interesting, over 30% you almost likely get crammed down in later rounds. This also has the advantage in that it encourages the founder to raise more money, because if they raise more money they’re not diluting themselves, and they’re reducing the risk for the investors. The more money you raise the less risk – because you can fail, you can do other things, you have longer runway.

How much runway do you like a company to have coming out of the Seed round?

I want the funding to last a minimum of 12 months, preferably 18 months.

You mentioned how you have rigid rules around how much equity is given away in a Seed round – that 20-30% range you described. Is it a tension for you balancing that rule with the “fear of missing out” on the next Uber, say, if only you’d been willing to go to 19%?

It’s not hard for me. I’ve been doing this for 20 years. In my first 10 years I would do that, and I had a 90% failure rate, which is pretty standard for what I do. My last 10 years my failure rate is 25-30%. By having a disciplined approach, you tend not to overpay, and overpaying is your main risk factor. I don’t ever value a company, it just has to meet my criteria – that it’s big enough to provide 10x return potential.

What’s your average initial check size?

$100K is what I normally do, though I’ll do a few $50K and over the life I’ll put in $500K.

I’m curious about rules of thumb for the angel world. You often hear in VC that each investment needs to have $1bn-plus potential in order for it to make sense for VC economics. Is there anything similar in angel investing, where each investment you make you have to believe it can become X?

The way I describe it is, each investment needs to have at least a 10x return potential, and you need to make at least 10 investments. If you’re going to do $25K investments you need to have at least a bankroll of $250K; hopefully you have like $500K and you can put $50K into 10 opportunities. Out of that, you should get one that’s worth 10x or greater.

The way the economics work, on ones that are successful you have the opportunity to further invest. Your subsequent dollars are not going to be the big winners but they’re going to add incrementally to your return. It also ensures you maintain an insider’s look into what’s going on, and that’s what matters in this world.

What are the essential rights or protections an angel needs?

The only rights I want one are prevent a recapitalization – I want to have the ability to veto a recapitalization or founders issuing more stock, as well as founders taking excessive salaries. You’ll usually get participation rights for the next round to maintain your positioning.

If the other investors want other special rights like preferences I will not invest. I want as clean vanilla as possible, so when a VC looks at it they say there’s nothing here to analyze, take out or modify.

How often does that happen that you’ll co-invest with other angels and they’ll ask for the kinds of rights and protections that you know will cause problems when VCs enter the picture?

That’s only occurred once in the last 10 years. What occurred is, a founder offered me standard terms and I agreed to them, signed off on it. He had eight other investors that he went to and got their input, they all provided some special things they wanted. When it got back to me six months later, I said, “I won’t invest if that’s in there, so please take all the changes out.” They did, and the company got funded with a standard agreement and they subsequently got another round.

Because I get so much deal flow, when stuff like this tends to happen, I just walk away. I don’t want to waste time negotiating with other investors. The rule is, somebody emerges as the lead investor, and then you follow the lead investor. It’s not a committee approach.

As an entrepreneur you often hear that VCs don’t want a messy cap table. At what point does the number of angel investors become problematic in your experience? How many is too many?

I’ve never had that as a problem as long as it’s clean; that is, it doesn’t have too many classes. Sometimes the VC will say, “we’ll convert everybody at this formula in this round to clean it up.” It’s the special terms; somebody may have a consulting agreement or an extra preference, it’s those things that have to be cleaned up and in many cases, those people have some sort of veto right.

One company, in which I invested had some of these special terms, so what the VC said was, “I want 100% agreement and it has to reach my desk by noon Friday or I’m walking away from it.” It was a friendly thing, but it was, “hey guys, we’re not going to be playing games.”

Back to the website – you further describe yourself as a “Renaissance Angel,” which you define as “intellectuals who pursue Angel investing for knowledge and satisfying experiences. Their portfolios are very diverse and eclectic having no discernible patterns. Financial returns are of secondary importance.” Start at the top – what are the bits of knowledge and satisfying experiences you gain out of angel investing?

I learn about different industries, different business models, different people, different cultures – it’s a constant learning progress, which is very satisfying to me.

I especially like young people who challenge the existing norms and are successful.

Talk about the “no discernible patterns” bit. There has to be some pattern, no? Something you routinely look for?

No.

Then what do you look for in a company that makes you decide to invest?

I’ll give you two examples, one I invested in two weeks ago called TwoSense. It’s an ERA [Entrepreneurs Roundtable Accelerator] company, they authenticate your smartphone to you, so if someone walks away with it we’ll notify you at some central location or email or phone. This will allow you to eliminate a lot of the passwords, because they authenticate you. It’s hard to place that one in any category.

The other one I have unmutes muted TVs, like at airports, sports bars, gymnasiums, doctor’s offices. It’s called Tunity. We have over 1M downloads. Initially we were going to do the second screen as our monetization, but we discovered out-of-home Nielsen ratings, and that’s much bigger. We’re providing SDKs to the people doing second screens, because we can now sync the actual show to the second screen.

Then a previous company was Monaeo, a tax jurisdiction company. We track which states you’re in and for how long, and which countries. There’s tax implications for how much time you spent in a city or country, and we report all of that. You don’t do anything, it’s all automatic.

So, you can’t discern a pattern here.

I can’t discern a pattern by space or industry. What I wonder is, are there commonalities at the level of the founding team? Is there something you routinely need to see from the founders, say, or elsewhere in the company in order to invest?

I try to do new markets or totally disruptive markets. The way I analyze the people is by the way they submit their one-page executive summary. It has to be clean, aesthetically pleasing so I can read it and enjoy it, it has to indicate explicitly what the company does, not what the company enables, it’s got to give me explicitly what you do. You have to tell me why you think the market is big, a little bit about yourself and how you plan to make money.

So that’s the basis. I spend one minute per summary. I either flush it or I ask for a meeting – that’s the one common thing. With people, I need to discern from them that they have vision, that they’re organized and they can describe things.

The last thing, stuff I don’t really care about is the product or service. I figure if you have this and it’s a reasonably meaningful product or service it’s an investible company.

For the company that has passed the one minute review test, now they’re meeting with you – what do you need to see in that meeting to get it over the line?

I need to be able to get along with the people. I need to find them smarter than I am in this area. It has to be a pleasant experience, essentially.

How many companies do you invest in in a given year?

Roughly 5-10. It goes in bunches; this year I’ve only done one, but in June/July I may do six. It’s not a bell distribution.

You receive 4,000 pitches annually, which I perceive to be a lot for an angel investor. What are your primary sources, and what deal flow hacks do you recommend for a new angel?

My first 10 years it was very hard to find companies. It was not a mature ecosystem, but then AngelList came out and they had 3,400 companies, so all of a sudden I had a big supply.

Then the accelerators came on and all of a sudden you had a large number of fundable companies. Then once I got into the network and got a name, I got a tremendous number of referrals from past founders, even failed founders, and through my network. I also get a large number of introductions from LinkedIn, which is usually of very poor quality.

It’s primarily referrals, accelerators then AngelList, but I haven’t gone to AngelList for new companies in a while, I’ve got too many coming in. Finding companies should not be a problem for anybody if they’re willing to research it and go to demo days.

You’ve invested in over 80 companies over your 20-year career as an angel investor. How does investment 81 differ from investment 1? What’s different about you as an investor now versus when you started>

The big difference initially was I was looking for companies where I could add a lot of value, which is what a lot of investors want to do – they want to be involved. What I found out is, if the company was going poorly I’d spend more and more time. So I plotted my involvement with the rate of return, and it was a big negative rate of return.

Over my last 10 years, I basically said I’m going to stop doing it, I’ll invest in high quality people, and if the company’s going bad, I let it go bad. I don’t spend extra time on a bad company; I actually spend more time with the good companies and helping them accelerate. The big difference is I’m not looking to add value, and I only provide assistance on an as-needed basis. Founders respect my time but when they do have questions, they’re real questions and I answer them immediately.

The key thing is I learned how to walk away from companies. That’s the biggest thing for an angel investor in terms of managing risk. Every new investment is based on the current time not the previous investment.

Are there particular areas where you try to add value?

The biggest value I do is introduce my companies to people. I do have a very large network, including in the corporate world. I can get executives at big corporations to mentor people and help out. I also introduce them to my other companies, which could be a benefit to them.

You’ve written a guide to angel investing. What compelled you to write it?

People were asking questions and instead of trying to answer each one individually, I decided to write it. It’s not been updated at all, so I’m looking to do a massive upgrade. I wrote it 6-7 years ago, maybe more. The new one will have some of the newer stuff I’ve run into with additional insight into what’s going on.

What are the classic mistakes entrepreneurs make?

The first, which doesn’t occur very often, is after I invest I find out the founder is quite dumb, and you know you’ve lost it all immediately. The person spent two years honing their pitch; they got you to invest based on the experience they had in pitching and then you find out they’re not functional.

The other big thing are the operational issues. Whether it’s people, scaling up – a lot of times, people will hit brick walls at certain revenue points, and there’s nothing you can do but bring in other people or completely reorganize.

If you identify you have a founder who falls into that latter category, the person who was great at the earlier stages of the business but is no longer the right person, do you feel it’s your role, as their investor, to address that with them? Or is that a judgment they have to come to on their own?

In general it’s very hard to bring in new people to a startup that’s failing or not doing quite well. You can promote from inside or do a reorganization where the founder has less management, but in general you don’t focus that much on that company – it’s a lost cause for the most part.

What are the mistakes angels make when they first start investing?

The ones that make the biggest mistakes are the ones I call the tourist angels. Those are successful business people who have cashed out or left public markets with a big stash of money, and they feel that just by throwing money around they’re going to make tons of money. They’re indiscriminate, and I’ve seen people lose it all. That’s one problem.

The other problem is, new investors sometimes are willing to take a 20-30% return on their money until they get hit by the losses, and then the losses just clean them out. They overpay for the potential return.

The other big problem is, a lot of investors will try to save their initial big investment by investing more and more and more. I’ve seen one guy who invested $50K and then over the next two years put in over $1M, and it was a complete loss. It’s basically not being able to manage the risk. You get emotionally attached to a company; you cannot be emotionally attached.

How has the New York tech ecosystem changed in the years you’ve been an angel investor?

The first 10 years it was hard to find companies; there was only one real angel group then, which was the New York New Media Angels (NYNMA), which became New York Angels. It was a very closed system; all the investors in my early companies I knew. In most cases I was the lead investor.

When AngelList came on with a large number of companies, you then had access to worldwide angels. So all of a sudden I didn’t know intimately those angels who were investing with me, so it was much more anonymous. I knew them by reputation or email, but most of them I’d never met. I’d see them at conferences and run into people who were investors in my companies. So it all became much more anonymous.

In my first 10 years I had to do all the raising of money. When AngelList came out the founder did all of that through the social network part of AngelList. That was a quantum step.

The next big step was the accelerators. They produce tons of people, and if you mentor them or help out, you can see the progress of the companies when they get in and when they get out, and that’s very valuable. You can see the progress they make or do not make. Plus they’re subjected to all of these diverse suggestions and how they filter them or correlate them to come up with their final product is very interesting.

And now with all the work spaces like WeWork and so forth, there’s massive numbers, it’s like you’re in startup heaven.

You were part of New York New Media Angels, are you part of New York Angels or other groups?

I didn’t join New York Angels because they went further upstream. And the other reason is I don’t get along with people. I’m not a member of any angel group. Bizarrely, I help jumpstart them, get them off the ground and organize them, but I did not join them. They do much later stuff essentially, so it’s not of any interest to me.

For the founder looking to raise money from an angel investor, what should they look for in conducting their own due diligence on their new potential investor?

They should get references from other founders, which is seldom done. Look at the investor’s previous investments, see the successes, and find out how they operate. There are investors who are helicopter investors, and you don’t want that. You have to remember it’s your company, not the investor’s company.

You say you typically invest in industries you know little about – how do you get comfortable with an investment opportunity in a space you may not know as intimately?

I generally deal in new markets, so there are no industry standards. I’m dealing with people who are disrupting the industries they operate in, which means they have a different way of doing things, so industry knowledge is a handicap. It has to be a good idea, big enough, and people who are running the company have to understand what they’re doing.

Does that suggest that you do then want somebody with industry experience?

I have a strong desire to invest in founders that have no industry experience. I can describe it in terms of the fox and the hedgehog.

A typical company that a VC invests in or an angel group, everybody’s got experience, 20-30 years – they’re all hedgehogs, experts in their area. In a fox world you want all your technology people, your CMO, your salespeople, your logistics people to be experts and hedgehogs, but you want one fox to provide the vision, to find ways to disrupt the market. Normally those are not people from the industry. When I looked at all my companies that were truly disruptive, not one of them had any industry experience.

The people with industry experience are acculturated with ways the industry works. They’ll tell you how you can’t do this, you have to do this, that’s how the industry works. Young people just out of college don’t understand that and can provide better ways of doing it.

You mentor a variety of women’s groups, including Astia, Springboard, 37Angels and The Vinetta Project – how did that come to be a passion for you?

It just occurred. The number of women coming in has dramatically increased over time; there was a need for mentorship and I supplied it.

Quick hits:

Favorite book and why?

I don’t read fiction because I get enough at work.

I’d say Clay Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma. I met Clay Christensen, and a lot of what I do is based on that idea that you never fear the big companies, because the little companies will totally disrupt them. For the big companies it’s like they’ve got a hundred little rats biting all over their bodies trying to get a piece of the action, and no VP in history ever got promoted by crushing rat number 73. Until you poke them in the eye they’re not going to respond to you.

A VC or angel investor I admire and why?

Fred Wilson. He’s got a premise that he sticks with. He’ll go a year or two without making any investments until stuff comes around that meets his premise. The discipline he has and the success he has is spectacular. Plus he blogs a lot and shares his knowledge.

Spaces I’m watching closely in 2017?

The things that interest me are deep learning and big data. The IoT thing with sensors, primarily, is rapidly increasing. Blockchain has been around and I’m not that into it, but somebody is going to win the Blockchain race.

In 10 years, how will the world we be different from a how-we-live-our-lives perspective?

I crowd source that answer from my founders. They tell me where the world is going.

You travel a lot – favorite travel destination?

I like Japan a lot and Thailand, for different reasons. I love London, England, but just generally other places are always nice – they’re learning experiences for me. I do a tremendous amount of travel. This year I’ll be going to Cuba, part of the Wharton program, we’ll have educators and people who know the culture and history and so forth.