The brain is an electric organ, and its 86 billion neurons communicate via pulses of electricity. When a voltage change causes one neuron to “fire,” it releases chemicals that trigger voltage changes in connected neurons. The brain’s every operation, from automatic functions like maintaining a heartbeat to cognitive processes such as making sense of these words you are reading, can be understood as a flickering pattern of electrical activity, with neurons firing along specific pathways.

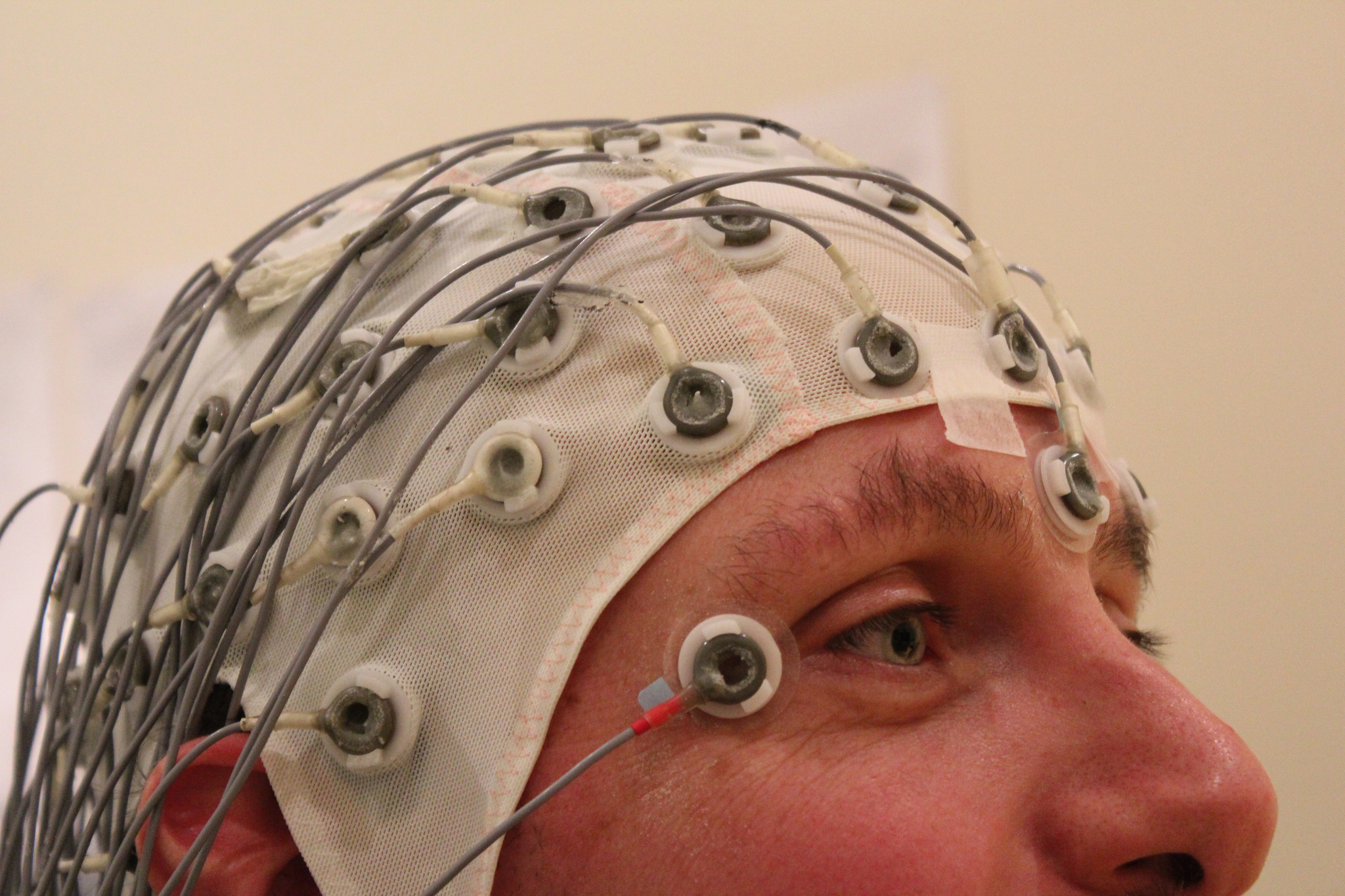

A researcher at Arizona State University (my alma mater) has discovered how to control robots using the human brain. A controller wears a skullcap outfitted with 128 electrodes wired to a computer. The device records electrical brain activity. If the controller moves a hand or thinks of something, certain areas light up.

“I can see that activity from outside,” said Panagiotis Artemiadis, director of Arizona State University’s Human-Oriented Robotics and Control Lab. “Our goal is to decode that activity to control variables for the robots.”

As an example, a user can move aerial drones by just thinking about decreasing the speed and distance between the devices as the wireless system sends the user’s thoughts to the robots.

“We have a motion-capture system that knows where the quads are, and we change their distance, and that is it,” Artemiadis said.

Up to 4 small robots, some of which fly, can be controlled with brain interfaces, eliminating the need for multiple joysticks and programming.

“You cannot do something collectively with a joystick,” Artemiadis said. “If you want to swarm around an area and guard that area, you cannot do that.”

To make them move, the controller watches on a monitor and thinks and pictures the drones performing various tasks. Artemiadis has been working on the brain-to-machine interface since he earned his doctorate in 2009, specifically on neural interfaces with robot hands and arms.

“During the last 2-to-3 decades, there has been a lot of research on single brain/machine interface, where you control a single machine,” Artemiadis said. This is not the first example of mind-controlled robots that have been tested with people with disabilities (see previous post). In fact, in 2012 a woman who lost the ability to use her limbs after a debilitating stroke had a BrainGate chip inserted into her brain to control a robotic arm to regain some level of independence.

Now Artemiadis’ discovery enables multiple robots to be able to be controlled by single thought patterns.

“I was surprised the brain cares about swarms and collective behaviors,” Artemiadis said. “What I did not know — or hypothesized — is that the brain cares about things we are not doing ourselves,” he added. “We do not have a swarm we control. We have hands and limbs and all that stuff, but we don’t control swarms.”

In other words, our brains are not used to all of our fingers and toes running off on their own and then returning.

“I was surprised the brain cares about that, and that the brain can adapt,” Artemiadis said.

The next step in Artemiadis’ research is multiple people controlling multiple robots. He plans to move to a much larger experimental space to refine the proof of concept. In the future, he sees drone swarms performing complex operations, such as search-and-rescue missions.

Artemiadis’ research is part of a larger technology trend of utilizing the untapped properties of our minds to control other aspects of our lives from performance enhancements to overcoming physiological disabilities. All one has to do is scan through message boards, like Reddit, to see programming tips on electric brain stimulation, titled transcranial direct-current stimulation or tDCS. People’s posts include advice on making and using homemade tDCS systems to treat a variety of disorders such as depression, anxiety and chronic pain.

Now entrepreneurs are bringing out commercial devices, hoping to launch an entirely new category of wearables. These startups do not make overt medical claims, so they have avoided the scrutiny of government regulators thus far. (If you are merely curious about research studies that use tDCS to treat depression, well, they are happy to provide information, including detailed charts of electrode placements.) But, the dozen or so companies in this nascent market are bolder in declaring how their products make healthy people even better. Last year, more than 600 tDCS studies came out. The range of research is staggering, because there are as many potential applications as there are brain regions to target. Investigators are testing tDCS as a treatment for disorders such as addiction, ADHD, Alzheimer’s, aphasia and autism — and that is just the As. In another line of inquiry, scientists are trying to figure out if tDCS can influence mental processes such as creativity, morality, learning and memory.

“There are tDCS devices that claim to basically make you a superhero,” said Hannah Maslen, a bioethicist who studies brain-intervention technologies at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Neuroethics. “Some of the claims they make are not even theoretically plausible from a neuroscience point of view.”

While tDCS has been studied extensively in carefully controlled lab conditions, it is tough to translate sensitive neurotechnology into mass-produced consumer gadgets that work without fail for every user, every time. One of the few independent studies of a commercial brain-stimulation gadget looked at the first product from the London-based startup Foc.us. According to the company’s marketing, the device improved attention and memory to make users better at video games. Yet, researchers found exactly the opposite effect: When subjects used the headset while performing a memory task, they actually did worse.

This past summer, athletes at the Rio Olympics started to use a tDCS device called Halo to pair their mental stimulation with physical training to get a winning edge on the competition. The company says its product can make people faster, stronger, more nimble or better coordinated. But, such initial successes raise a question: Does brain hacking constitute brain doping? The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) compiles the list of performance-enhancing substances and treatments forbidden by the International Olympic Committee. Olivier Rabin, WADA’s science director, says his team is “very actively monitoring” brain stimulation technologies and recently discussed whether tDCS and similar techniques warranted inclusion on the prohibited list. Their verdict: It is not yet time to make that decision …

Image credit: CC by Tim Sheerman-Chase