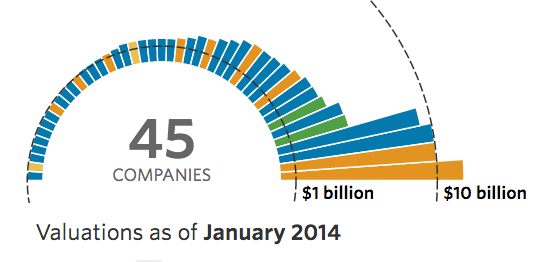

Ever since the word “unicorn” was coined, the startup world has been obsessed with them. The bigger the unicorn, the greater the obsession (e.g. Uber). Even the Wall Street Journal is in to it, with a great dynamic graph. Starting with January 2014 when there were just 45 Unicorns, and Uber’s valuation was a quaint $3.8 billion:

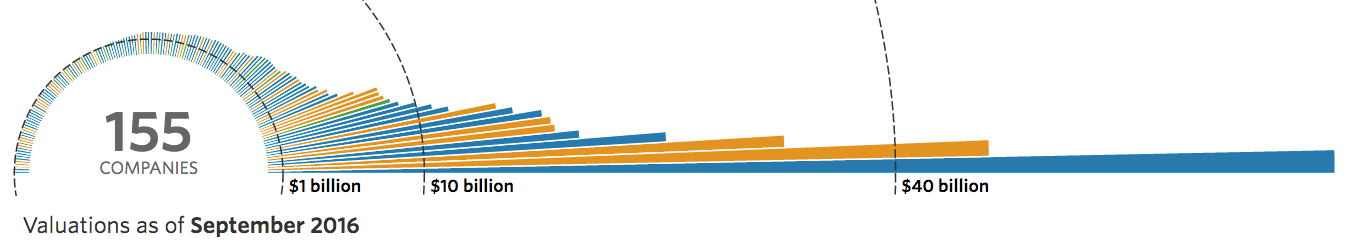

To the present day …

The Wall Street Journal’s 27 second interactive movie shows a month-by-month progression of the world’s rapidly growing unicorn population.

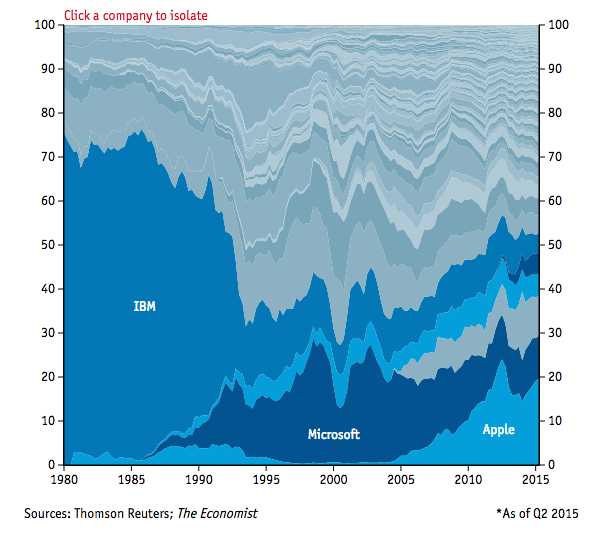

For multiple reasons I have a greater fascination with the market caps of public companies. First, public market valuations change constantly. In February I wrote a piece “Lessons Learned From Google’s 42 Hour Reign As The World’s Most Valuable Company.” In that piece I featured this graph showing the top 100 tech companies by market cap over time.

Second, public market valuations are real, they are not “preferred” valuations, which often grossly overvalue the real value given the downside protection of preferred.

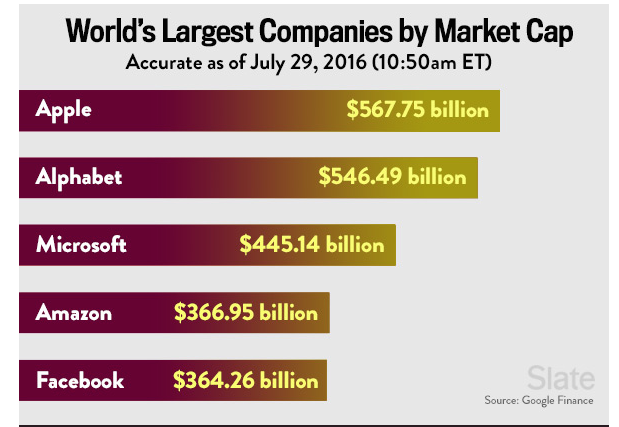

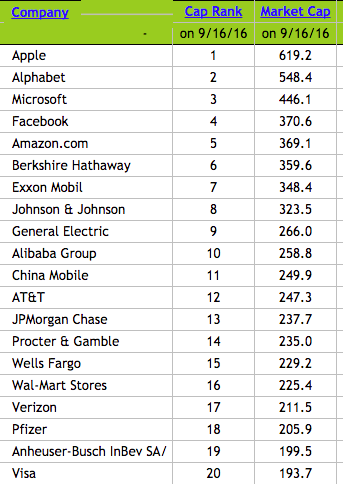

Finally, public market companies are much bigger. As of the close of trading on September 16, Apple’s market cap was $619 billion, 9x bigger than Uber’s last (inflated) preferred valuation of $68 billion.

So given my reverence for public market caps, I thought it was a profoundly seminal moment when, on the morning of July 29, buoyed by strong earnings, Amazon and Facebook surpassed Berkshire Hathaway and Exxon, and, for the first time in history, all 5 of the largest market cap publicly traded companies in the US were “tech” companies:

A month and a half later, the top 5 remain the same:

On one hand, this is a huge milestone for the tech industry. This is further confirmation of Marc Andreessen’s prophetic WSJ piece written more than five years ago “Software Is Eating The World.”

On the Other Hand …

There was recently a compelling article in the New York Times titled “At BlackRock, a Wall Street Rock Star’s $5 Trillion Comeback.” The article highlights that Lawrence Fink, the founder of BlackRock “ … has transformed BlackRock from a bond shop catering to pension funds and insurance companies into an asset-gathering machine that uses advanced technology to reimagine how investors buy, sell and assess the risks of a wide variety of securities.” Later, the article stated that, “Some analysts, in fact, argue that BlackRock should be valued as a technology company, as opposed to an asset manager.” Meaning that BlackRock deserves a higher multiple on its earnings because it is not an asset manager, it is a tech company.

The “other hand” that I am referring to is the increasingly true fact that every successful company is a tech company. Just like every successful company started using electricity, and every successful company started using the telephone, every successful company is obviously deeply engaging with software. Companies that are most adept at imagining, developing and deploying software are increasingly determining the winners and the losers in every industry — as in Blackrock’s case.

Is Amazon really a tech company, or are they really a retailer leveraging technology (taking AWS out of the equation)? Is Blackrock a technology company, or are they an asset manager leveraging technology?

Because if Amazon is a “technology” company, and Blackrock is a technology company, then every successful company will be a technology company. What percentage of Exxon’s oil production comes from deploying new technology (i.e. fracking)? G.E. has been mocking Silicon Valley in TV commercials as it touts itself as a tech company to both recruits and investors.

So was this a seminal moment “tech companies” emerging as the dominant force in our economy,” or was it just further validation the most successful companies will have tech as their core competency? Does the difference even matter?

Maybe these are just signposts on the road to Singularity. Maybe software is not “eating the world,” maybe, increasingly, software “is the world.”

Image credit: CC by Scott Schopieray