Recently, Suki Bagel, a 12-week-old Border Collie arrived in our house. Suki was so excited to be united with her new family that she peed on our kitchen floor. Seeing my disappointment, my wife retorted, “what do you expect, she’s not a robot?” I replied that AIBO never peed.

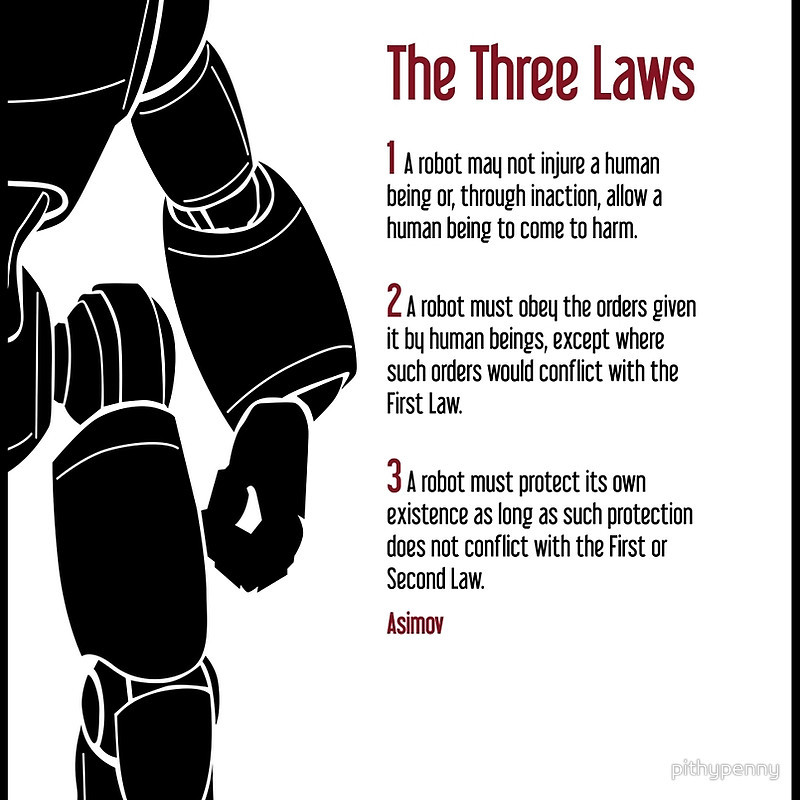

As our lives are quickly becoming more intertwined with robots, we need to remind ourselves of Asimov’s three rules and what we are doing to proactively protect ourselves from violators. His three principals from his novel “I-Robot” can be seen in the graphic below (you can even order the t-shirt):

Today, I would like to focus my post on the first law – human injury. Two years ago, when Rodney Brooks first launched Baxter, a lot of work and salesmanship went into convincing the manufacturing industry that “collaborative robots” are indeed safe enough to work alongside humans, see video below.

Industrial robots for the past 30-plus years have been largely isolated behind safety fences, but now, robots like Baxter are safe and smart enough to work with people. By taking over tiresome and repetitive tasks, these robots are replacing dumb jobs on the production line, freeing humans to do tasks that require manual dexterity and ingenuity rather than extreme precision and stamina. These robots are also increasing productivity and output, which lead to more cash for jobs.

For example, BMW first introduced robots to its human production line at the Spartanburg, SC plant in September 2013. The robots that were originally made by Universal Robots were relatively slow and lightweight to make them safer around humans. In May of 2015, Universal Robots was acquired by Teradyne for $350 million. According to then vice president of assembly at the Spartanburg plant, Richard Morris, the robots replaced a task on the line that was causing repeated injuries to human workers. The robots were able to perform these tasks more quickly (no surprise) and efficiently (without injury). However, concern rose as the robots could not be easily slotted into other areas of the human production line because they are complicated to program and set up and, most importantly, dangerous to be around. [shameless plug: my latest portfolio company, Carbon Robotics (photo below) aims to change all that…]

Robots have caused at least 33 workplace deaths and injuries in the United States in the last 30 years, according to data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. That may not sound like many, but the number may well understate the perils ahead. Unlike the robots of yesteryear, which were generally in cages, the new robots of Baxter, Carbon, and UR have much more autonomy and freedom to move on their own.

“In order for robots to work more productively, they must escape from their cages and be able to work alongside people,” said Kent Massey, the director of advanced programs at HDT Robotics. “To achieve this goal safely, robots must become more like people. They must have eyes and a sense of touch, as well as the intelligence to use those senses.”

Many researchers are attempting to teach robots this sense of touch and empathy to avoid human injuries. In Germany, Johannes Kuehn from Leibniz University of Hannover told the IEEE that they are researching technology to enable robots to process pain. These researchers think pain-sensitive robots are worth developing so they can keep themselves—and the humans working with them—safe from harm. If there’s a threat to a robot’s gears or motors, for example, it can take evasive action.

“Pain is a system that protects us,” said Mr. Kuehn “When we evade from the source of pain, it helps us not get hurt.”

With that in mind, Kuehn and his colleague Sami Haddadin are developing what they describe as an “artificial robot nervous system” for the job. For the system to work, it needs to be able to both sense sources of pain (like a flame or a knife) and figure out what to do about it (an appropriate reflex action). The pair are using the human nervous system as their inspiration. They have tested out some of their ideas using a robotic arm with a fingertip sensor that can detect pressure and temperature. It uses a ‘robot-tissue’ patch modeled on human skin to decide how much pain should be felt and what action to take. If the arm feels light pain, it slowly retracts until the pain stops, and then returns to its original task. Severe pain, meanwhile, causes the arm to go into a kind of lockdown mode until it can get help from a human operator.

Keeping people safe is just as important, Kuehn and Haddadin say, especially as we are likely to see more robots operating alongside human workers in the coming years—if a robot is taught to recognize and react to pain, it can warn everyone around it.

“Getting robots to learn is one of the most challenging things but is fundamental because it will make them more intelligent,” robotics expert Fumiya Iida of Cambridge University in the UK, who wasn’t involved in the research, told the BBC. “Learning is all about trial and error. When a child learns that falling over causes pain, it then learns to do it with more skill.”

This isn’t the first time researchers have decided to try to humanize robots. Earlier this year, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) started teaching robots empathy by making them read children’s books, which is just one of many other DARPA projects that aim to make robots understand right and wrong.

Until recently, regulations have required that the robots operate separately from humans, in cages or surrounded by light curtains that stop the machines when people approach. As a result, most of the injuries and deaths have happened when humans who are maintaining the robots make an error or violate the safety barriers, such as entering a cage. But the robots whose generation is being born today collaborate with humans and travel freely in open environments where people live and work. They are products of the declining cost of sensors and improved artificial intelligence algorithms in areas such as computer vision. Along with the new, free-roaming robots come new safety concerns. People worry about what happens if a robot spins out of control illustrated by recent headlines of Tesla’s autopilot crash or the K5 mall-security robot that ran over a toddler.

One of the biggest areas of concern in robotics is the proliferation of drones and their ability to disrupt the national airspace and fall from the ski. There are already countless examples of drone near misses with airplanes, people and even the White House. If last mile UAV delivery in the US will become as commonplace as FedEx or UPS trunks, then we have to create secure routes and invisible fences around sensitive areas such as airports, power plants, and stadiums.

Earlier this week, Airbus announced a strategic partnership with Dedrone, a company that specializes in drone detection, to bring its technology, which is already being deployed at sports stadiums, to airports. Dedrone’s sensor technologies (below) have been successfully used at Citi Field, home of my New York Mets, as well as prisons, oil-and-gas facilities, and other sensitive areas that want to keep unauthorized drones out.

Generally, these venues install Dedrone sensors, which resemble CCTV cameras facing the sky. The sensors perform frequency scanning, image analysis, or just watch and listen for activity up above. If they detect a drone, the system alerts security people on the ground, with directional information, the altitude of the aircraft to successfully disable the UAV. The market for drone security services is quickly growing; Dedrone has a handful of competitors including DroneShield, Drone Detector and SkySafe. Many are working on active drone deactivation and invisible fences to quickly deactivate aerial trespassers.

As I walk the dog in the unbearable humidity of Manhattan, I see a drone fly overhead, and I am thankful for those warm puppy eyes that hopefully will develop empathy for my belongings (and me).

Image credit: CC by Bethany