A few months back, I went to the Mets playoff game at CitiField. Driving home at 12:30 am, I was exhausted, which led me to accidentally turn the wrong way on Amsterdam Avenue. Clearly, my car (via GPS) knew that I had made a mistake, but why wasn’t there some early warning signal like my blindspot detection?

Until then, Bioengineers at the University of Illinois at Chicago have developed a mathematical algorithm that can “see” your intention while performing an ordinary action like reaching for a cup or driving straight up a road—even if the action is interrupted. The study is published online in the journal PLOS ONE.

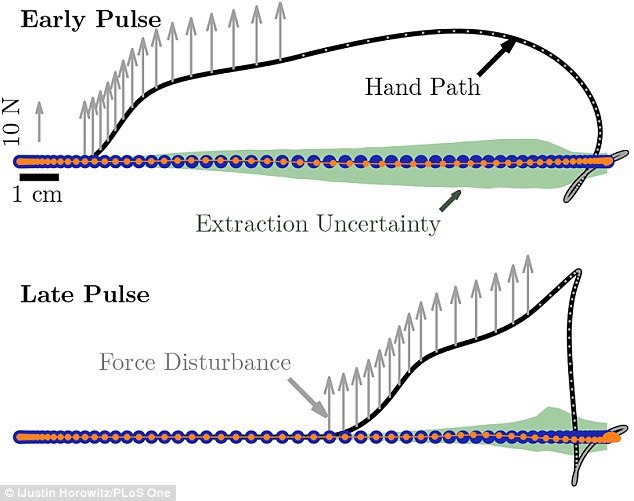

“Say you’re reaching for a piece of paper and your hand is bumped mid-reach—your eyes take time to adjust; your nerves take time to process what has happened; your brain takes time to process what has happened and even more time to get a new signal to your hand,” said Justin Horowitz, UIC graduate student research assistant and first author of the study. “So, when something unexpected happens, the signal going to your hand can’t change for at least a tenth of a second—if it changes at all,” Horowitz said.

In a first test of this concept, Horowitz employed exactly the scenario he described—he analyzed the movement of research subjects as they reached for an object on a virtual desk, but had their hand pushed in the wrong direction. He was able to develop an advanced mathematical algorithm that analyzed the action and estimated the subject’s intent, even when there was a disturbance and no follow through.

The algorithm can predict the way you wanted to move, according to your intention, Horowitz said. Taking this once step further with autonomous automobiles, a car’s artificial intelligence would use the algorithm to bring the car’s course more in line with what the driver wanted to do.

“If we hit a patch of ice and the car starts swerving, we want the car to know where we meant to go,” he said. “It needs to correct the car’s course not to where I am now pointed, but [to] where I meant to go.” “The computer has extra sensors and processes information so much faster than I can react,” Horowitz said. “If the car can tell where I mean to go, it can drive itself there. But it has to know which movements of the wheel represent my intention, and which are responses to an environment that’s already changed.”

For a stroke patient, a “smart” prosthesis must be able to interpret what the person means to do even as the person’s own body corrupts their actions (due to muscle spasms or tremors.) The algorithm may make it possible for a device to discern the person’s intent and help them complete the task smoothly.

“We call it a psychic robot,” Horowitz said. “If you know how someone is moving and what the 1/2 disturbance is, you can tell the underlying intent—which means we could use this algorithm to design machines that could correct the course of a swerving car or help a stroke patient with spasticity.”

Predication: By 2050, it will be against the law for humans to drive an automobile in populated areas.

Image credit: CC by therobbotrabi