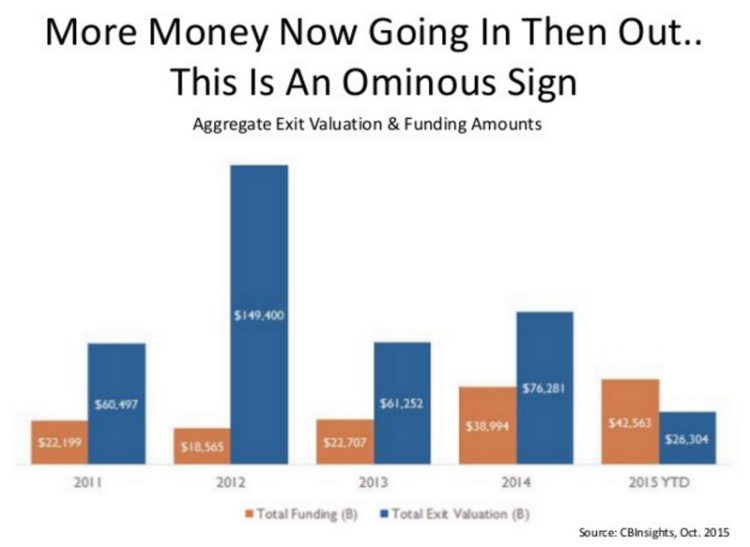

As a VC, I’ve been worried about the private market bubble for two years. I have a deck on SlideShare, “Are We In A Tech Bubble”, that I update every few months with all the data I find that is relevant to answering that question. When I updated the deck in October, there were two slides I found very worrisome. The first was:

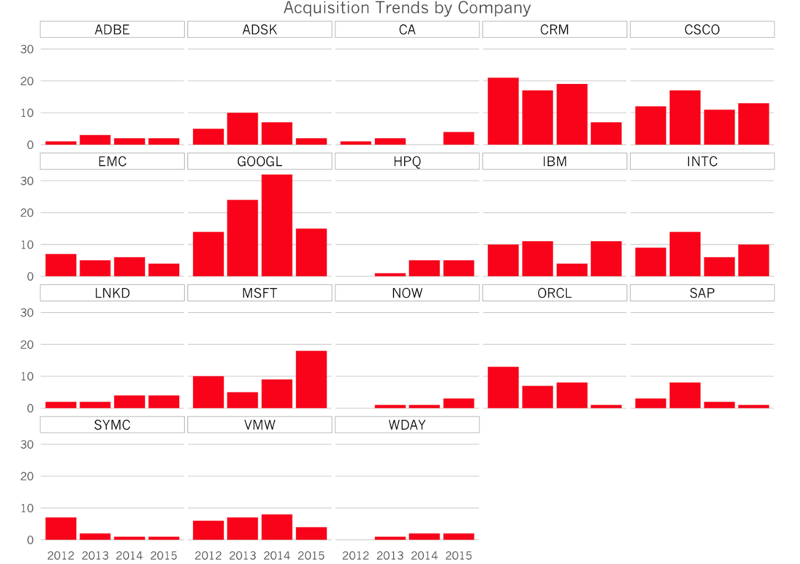

This is worrisome, because this is a trend that can’t continue for long. Investors like to get their money back. There are three simple reasons that more money is going in then coming out. First, VCs and others are investing more money in private companies then ever before (other than the peak of the last bubble in 2000). The second reason is that the number IPOs of VC backed tech companies are down 55% year-over-year. The third, and most worrisome reason, is that tech M&A is down 20%. This slide comes from a great post by Tom Tunguz that looks at the 20% decrease in M&A on a company-by-company basis:

Other than Microsoft, driven by the need of a new CEO to transform the company, almost every, most other major acquirers (Google, Salesforce, Oracle…) dramatically decreased the number of acquisitions in 2015. What lead to the decrease in the number of tech M&A deals this year?

My guess is, the reason is simple, most tech M&As don’t work out. In 2011, ina great HBR article, Clayton Chrisetenson wrote that “.. study after study puts the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions somewhere between 70% and 90%”. In January of 2015, McKinsey & Co. published an M&A study looking at the past decade of deal-making among top global companies. It found that among eight major industries, tech companies did the worst job by far of delivering shareholder returns through M&A, especially in big transactions. Given this failure rate, it’s amazing there’s are any tech M&A at all. But human nature leads us to beleive that we are the exception to the rule. Many tech exces think they have the magic touch necessary to turn M&A in to shareholder value. This has never been more true than the parade of Yahoo CEOs who continuously used their cash and shares to acquire 112 companies over the last 18 years. How did it work out? I think you know the answer.

Below is some simple analytics, putting Yahoo’s acquisitions in to three buckets. The first bucket is $100+ million acquisitions. There have been 21 of those. The second bucket are those M&A transactions where the prices were disclosed, and were less than $100 million. There were 27 of those. The third and final bucket are those M&A transactions where the price wasn’t disclosed. Generally, prices are disclosed when the prices is above $50 million. So I’m esitmating that the average price was $10 million. Probably low, but let’s give Yahoo the benefit of the doubt. There were 64 of those transaction.

Finally, since some of these transactions were done 17 years ago, I think it makes sense to inflation adjust them for purposes of this analysis. Per the analysis below, Yahoo has spent more than $25 billion, inflation adjusted, on its 112 acquisitions:

Wall Street analyst Rob Peck estimates that Yahoo’s core business is worth 6X 2017E EVITDA of $979, or about $5.8 billion. So if you assume that, less the acquisitions, Yahoo’s core business is worth more than $1 Billion, that means that Yahoo has destroyed more than $20 billion in its 18+ years of M&A folly.

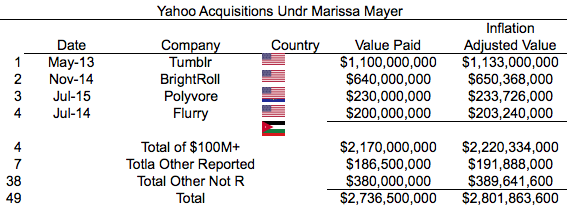

Obviously, most of this happened long before Marissa Mayer’s watch. Looking at Yahoo’s M&A since Marissa took control in 2012 yields the following:

If Yahoo is only worth $5.8 billion, it’s hard to believe that a big chunk of the $2.8 billion Marissa spent wasn’t flushed down the toilet.

The moral of the story is 1) tech M&A is hard, and Yahoo probably performed worse than average on it’s way to destroying $20 billion of shareholder value through M&A, 2) Marissa Mayer certainly destroyed some level of shareholder value through her M&A 3) private company investors should be scared of another weak year in tech M&A. Then again, corporate execs have pretty poor memories, and most think they’re from Lake Wobegon, which means most think they’re above average.