It’s not just VC — the proportion of women mutual fund managers has fallen, too.

- The proportion of women partners at United States VC firms has declined for more than a decade

- Studies, posts and task forces keep reinforcing the facts but suggest change will be hard

- And it’s not just VC: The proportion of women mutual fund managers in the US has fallen too, and to near identical levels

- Perhaps both are “mirrorocracies,” not the meritocracies many insiders think they are?

- The more we talk about this sort of groupthink, the more chance we have of getting out of it

One long-running source of concern voiced by many in the US Venture Capital (VC) ecosystem, especially female founders, has been the near-homogenous gender makeup of VC partnerships. The recent Babson study “Women Entrepreneurs in 2014: Bridging the Gap in Venture Capital“ concluded that the percentage of women partners in US VC firms had fallen from 10 percent to just 6 percent over the 15 years 1999-2014. —gender diversity has got progressively worse.

Dan Primark at Fortune reinforced this message with a recent piece that asserted “Women are not making progress in the male dominated VC world data shows.” His research shows women decision-makers in VC number, in fact, slightly less that 6 percent.

Acknowledging the importance of the issue last December, the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) announced the formation of a task force to help VC firms increase opportunities for women and minorities. It’s important to note that diversity in VC is not just a gender problem. As Vivek Wadwha wrote in the Washington Post, “this is a step in the right direction.”

Especially since the NVCA’s own VC-CEO Brand Gap survey, conducted by DeSantisBreindel, revealed the fact that most VCs don’t think that what their partnership “looks like” matters to entrepreneurs.

When asked if the gender makeup of a VC’s partner base matter to CEOs, 9 of 10 VCs said no. But 4 of 10 CEOs said it did matter, and 2 of 3 female CEOs said it mattered. So regardless of what outsiders think, this actually is a concern for VCs’ investee side clients. And, of course, the fact that VC’s don’t realize they have a problem is a big problem in itself.

Beating up on VC in this context is pretty easy given the data. And with women accounting for only 10 percent of all VC investment professional, the “pipeline” for future advancement is not substantial — so change is likely to be slow.

A word of caution when anyone starts talking about building the VC talent pipeline: Catalyst, in a much broader context, wrote about pipeline’s broken promise in 2010. They summarized the pipeline argument as: “Just give it time. Not yet but soon. When women get the right education, the right training, and the right aspirations — to succeed at the highest levels of business — then we’ll see parity.”

But they concluded: “If only that were true.”

In other contexts the pipeline argument, focusing on lover-level talent development and waiting for it to work through the system simply hasn’t translated into real change. Which is why, in the case of women on corporate boards for example, more assertive tactics have been deployed. These include the fine work of Helena Morrissey‘s 30 Percent Club through to legislated quota solutions. Deloitte has a great country-by-country survey of this.

In a bizarre — or maybe not — coincidence, the number of women mutual fund managers in the US has fallen every year for the last six years. So I think it is important for those who want to call out VC (which is well justified, in my view) to appreciate VC is not uniquely “challenged” when it comes to gender diversity.

The Financial Times has just reported “Female Fund Managers in Decline,” noting that the proportion of women mutual fund managers has fallen from just over 10 percent to under 7 percent. It’s mirroring VC not just directionally but even in terms of proportionate representation.

Ann Richards, CIO of publicly listed Aberdeen Asset Management speculates that the decline in her industry could be partly due to the erosion trust in large financial services firms generally as a result of the financial crisis. That may well be the case, though the same would not apply to VC. In fact, it’s the opposite, in my view.

As a result of the expansion of high tech entrepreneurship and some high-profile successes (so Aileen Lee’s Unicorn outcomes) it seems to me that VC’s public standing and appeal has substantially increased. On the flip side,some argue that the gender representation in the VC is a consequence of the decline (since 1983) of women studying computer science. The high in 1983-84was 37 percent; it is now less than 20 percent.

But that decline clearly doesn’t apply to the mutual fund land. Theproportion of women MBAs is rising. For example, the Harvard Business School Class of 2016 is 41 percent women; 10 years ago, the figure was around 35 percent.

So when it comes to factors at work here, it is important to understand that it’s complicated.

What do VC and mutual funds have in common that drives declining gender diversity? Are they both mirrorocracies?

For a start, the fact that VC and mutual funds are in a similar place does suggest that there is more going on here than narrow industry specific factors. One explanation could be that both are “mirrorocracies” as opposed to “meritocracies,” meaning that the majority of current leaders and the top tiers of the industry genuinely believe they pick the best of the best for their teams, but in reality, they are all captive to multiple cognitive biases — not least related to pattern recognition. Founder Stephanie Quilao responded to a Steve Blank post on women entrepreneurs:

The notion that SV is a meritocracy is false. It’s really a mirrorocracy. The VCs are funding and paying attention to mirror images of themselves. Just pull up the Team page or Portfolio page of any VC firm, or the speaker list page of any tech related conference here and what is the profile of the people you see? Besides gender, the mirror also applies to race, age, and educational background. Until the view in the mirror changes, the system will stay the same.

In each case, VC and mutual funds, has leadership “groupthink” created a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop when it comes to industry demographics? I think so. Which suggests that, in each case, finding ways forward requires breaking those loops — and that only can happen when you realize you have a problem, and talk about it a lot.

That is why the NVCA task force is so important for VC, and why it is encouraging when VivekWadhwa and others speak out, and why it is especially encouraging when influential insiders like Dave McClure at 500 StartUps and Paul Graham and the Y Combinator team lead by example and turn words into actions with their investees.

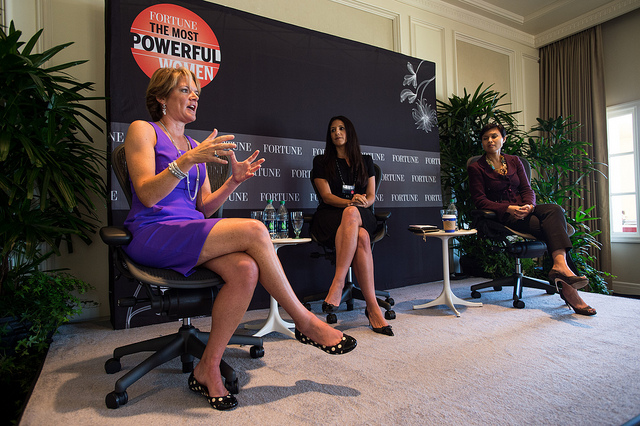

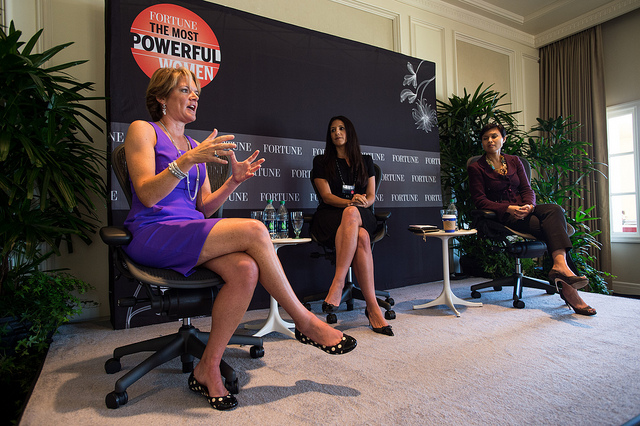

Photo credit: CC by Fortune Live Media