According to the bible, when the People of Israel would travel in the desert a “Cloud of Glory” would protect them from harm. Today the Land of Israel is protected by Iron Dome (a modern-day divine shield). As of today, Hamas has launched over 500 missile attacks at Israel this past week, and miraculously Iron Dome has had a 90% interception rate. Its success is a reflection of how robotics is making the world a safer place, as only a robot could respond within seconds to a rocket attack aimed at kindergartens, elderly homes, and apartment buildings.

So how does it work?

Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, an Israeli defense company, developed Iron Dome in collaboration with the Defense Ministry’s Administration for the Development of Weapons and Technological Infrastructure as well as Elta Systems, a subsidiary of Israel Aerospace Industries, the manufacturer of Iron Dome’s radar system; mPrest Systems, a subsidiary of Rafael, which developed Iron Dome’s command and control system; and Comtec Communications, which develops components for radio frequency communication. It should be noted that US aid helped support this development.

“The development of Iron Dome was based on knowledge accumulated at Rafael over 40 to 50 years of missile development,” says Uzi, the head of the Iron Dome project, who can only be identified by his first name for security reasons. “When you develop a missile, you take the knowledge you have and direct it toward the operational goal.”

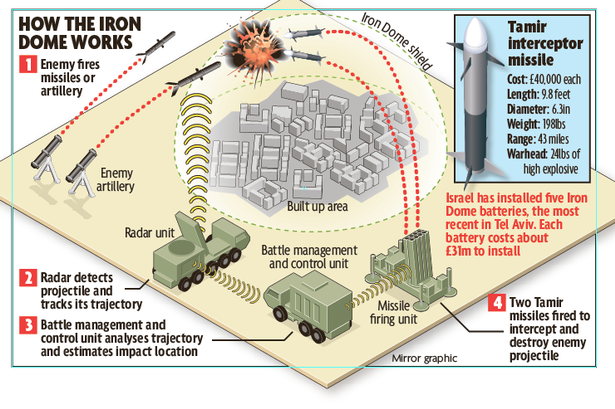

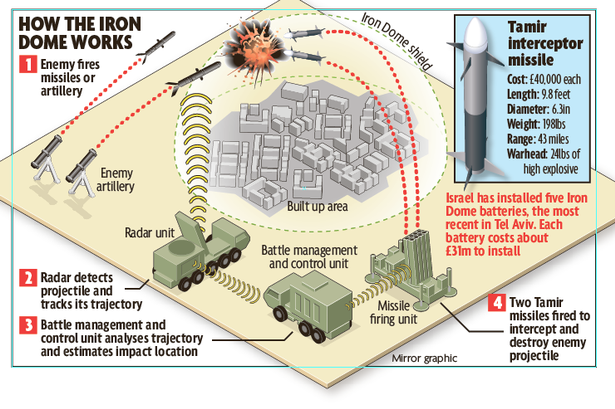

First the radar, developed by Elta, scans the area for a ballistic motor or rocket. When it detects action, it begins a process of information analysis and reporting that tracks the rocket’s location and determines the type of rocket. This info is transferred to the command system, developed by mPrest, which processes and assesses the level of threat and the rocket’s projected destination.

If it’s determined that the rocket will fall outside a protected area – meaning an area that decision makers have determined as high priority because of high population concentration or strategic importance – it won’t be intercepted. But if it seems the rocket will fall inside said area, the decision to intercept will be made. For short range rockets, that decision will be a split-second one. Literally.

The third component in the Iron Dome battery is the launcher, which includes 20 interceptors made by Rafael, which are operated by members of the Israeli Air Force’s Air Defense Command in the field. An interceptor can act independently; even if it loses communication with the ground, it can still complete its mission thanks to its sighting systems.

“Interceptors plan their own route from the moment they are launched,” Uzi says. “They get the trajectory and aim at the optimal place for interception.” The battery also has a communication center which connects all the launchers and interceptors in the region.

The (robotic) brain of Iron Dome, according to Uzi, is the command and control center which synchronizes info from the radar system and other sensors and decides which targets to intercept.

“From the moment the system detects the threat – a rocket that’s been launched – it detects the type of threat, whether it’s a Fajr or Qassam rocket or something else, and estimates its trajectory,” says Natan Barak, mPrest CEO as well as a colonel in the reserves and the former commander of the navy’s software unit.

“The moment we see that the threat is going to reach a protected area, we build the interception plans,” he says. “We construct hundreds of solutions and choose the best one. Then we launch the interceptor at the right time so it will meet the threat in the right place. We need to be able to tell whether it’s one threat or several. There’s a program to match each threat, and we confirm that the interceptor is carrying out the program we expected. If there’s a change in the data, the interceptor gets an update, and that’s how the interceptor meets the target.”

Before the moment of interception takes place, a series of decisions have already been made by policy decision-makers, the Air Force and other agencies.

“The number of decisions that need to be made in real time is very small once interception begins,” says Barak. The system can function automatically, but it lets operators intervene in a number of ways.

“There are many constraints because we’re operating the system in a civilian environment and in an area where aircraft are present,” says Barak. “These factors make interception relatively complex. At short ranges, which are the hardest for us, the reaction time from the moment of detection and the moment we know that the rocket is going to fall in a protected area has to be less than a second. We have less than a second to launch an interceptor.”

And if there’s more than one threat? “We have to launch more than one interceptor.”

Barak says that at this stage, the batteries are coordinated at the field-commander level. Each of the batteries is independent, though they communicate with each other. But if one went down, the others could compensate. But that scenario is unlikely. “The systems have extraordinary backup,” he says. “It’s rare for a system not to be in complete working order.”

Iron Dome isn’t influenced by Israel’s weather conditions and can operate even in inclement weather, says Barak. And good news for Tel Aviv residents: the greater the distance, the better the interception ability.

“The more time we have, the greater the precision,” says Barak. “So Gush Dan (the region where Tel Aviv is located) can be less afraid. Of course, many parameters must be considered, but in terms of this particular aspect, Gush Dan is easier for us than Sderot.”

“We use a very sophisticated algorithm to plan the interceptor’s path,” says Uzi. “Once the operator presses ‘confirm,’ the system does the optimization and decides when to launch the interceptor. After the launch, the interceptor receives ongoing updates about the target’s location, which it uses to tweak its trajectory so it can reach the optimal interception point.”

One of the considerations is whether to intercept the target outside a protected area. Even if the interception can only be done over a populated area, aerial interception is still considered the better alternative.

“If the target lands in a protected area, there will be a lot more damage than if it is intercepted and a piece of metal falls that can’t cause as much damage,” says Uzi.

Such was the case yesterday, for example, when a piece of a rocket intercepted over Gush Dan fell on a car, setting it on fire.

Iron Dome’s level of precision – which, according to Uzi, is 82 to 87 percent – has been further improved thanks to the experience Rafael gleaned from the battery’s operators on the ground.

Rafael officials say that the system was developed with cost efficiency in mind. “We were asked to develop a very inexpensive system,” says Uzi. “We invested a lot of money in developing the interceptor and the system in general. We did some very smart things and we tried to use very reliable components and systems. We also used a few innovations of our own that have kept costs down.”

Although Iron Dome does not have a perfect interception rate, defense establishment officials are pleased with its performance.

“The system’s capabilities are far beyond what we thought and expected when we started out four years ago,” says Uzi. “The plan was to hit rockets launched from 15 to 20 kilometers away, and now we have a system that intercepts rockets that are launched from 70 kilometers away and more. The system works beautifully. The excellent performance we’re seeing now is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Officials at mPrest take pride in the system’s sophisticated technology. “From a technological perspective, every one of its components is the only one of its kind in the world,” says Barak. “There is no interceptor like it on earth at this cost– not in terms of response time or the ability to expand the system. No other system can distinguish between various kinds of Qassam or Fajr rockets or other types of rockets and intercept them. The speeds are high and the interceptors are relatively small.

“There is no radar like this on earth because detecting these things is a very complicated business,” he says. “It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack – there’s a lot of noise and you have to be able to track the threat that’s in Israel. So there’s also a lot of interest in the system throughout the world.”

According to officials at Rafael, there are no other operational systems in the world that have proven as effective at short-range interception as Iron Dome. And back to the cost thing: “Our price is one-tenth of any other similar missile on the market today,” says Uzi.

The Iron Dome command and control center is a technological platform with a number of applications that can reconfigure its various components and reshape them to create new uses, kind of like using the same Legos to construct very different models. Founded in 2003, mPrest, which has 120 employees, also develops systems for the Israel Electric Corporation and for border defense.

Barak says this kind of flexibility enables the system to adapt to future needs. “With Iron Dome’s command and control system, we’ll be able to fight the next wars, too. We know what the threat is today, but we don’t know what it will be tomorrow. So we built a system that’s flexible, has fantastic response and real-time threat management ability,” he says.

The Iron Dome system, which was built to respond to Israel’s unique defense challenges, will be exported to other countries on a commercial basis, becoming a source of income. Barak points to potential applications like protecting troops in Afghanistan and guarding strategic areas.

“Rocket warfare will exist throughout the world, and this is the only way to protect against it,” Barak says. He also notes the untapped possibilities. “The system is just starting out. It has used maybe ten percent of its potential.”

Our thoughts and prayers are with the people of Israel and its brave defense forces that are guarding all its people, Jews, Muslims and Christians, from the harm of terrorists.