Recently, I was sitting with a leading robotist discussing driverless cars. We both laid out a vision of a world with special driverless lanes where cars will be moving faster going bumper to bumper than human operated vehicles. The quality life improvement for the elderly, blind, and handicapped would be tremendous. However, that was before Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx put the brakes on the autonomous revolution, or as his chief counsel declared, driverless cars are “a scary concept” for the public. I imagine that in 1890, Foxx’s counterpart said then same thing about motorcars replacing horses.

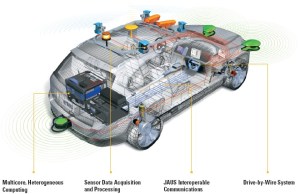

In a few years “autonomous drive” could be as common and inexpensive for car buyers as “hybrid drive” is today. Many of the predicate technologies are already in commercial use—adaptive cruise control, anti-lock brakes, rear-collision prevent, self-parallel-parking, rollover stability, pedestrian alerts. And as Google, Ford, Mercedes-Benz and many others have proven with their driverless cars, the enabling information technologies from all weather “seeing” to GPS and intuitive mapping have matured.

Yet the best we can get out of Washington is an announcement this month by Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx that the DOT intends to “begin working” on a regulatory proposal to someday require vehicle-to-vehicle communications for crash avoidance. Worse, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the DOT’s regulatory agency, is putting the brakes on the driverless revolution. NHTSA envisions years of further research and “does not recommend at this time that states permit operation of self-driving vehicles for purposes other than testing.”

Four states have already passed laws allowing the testing of self-driving cars—Florida, California, Nevada and Michigan. But if states pass legislation legalizing the public sale and use of self-driving cars, NHTSA says it will intervene to “evaluate their relationship to Federal Motor Vehicle Standards”—an unsubtle threat. Do you smell lobbyists at work here? I mean, who will the personal injury attorneys sue if a robot is driving the car?

As the WSJ declared, regulators should accelerate the introduction of self-driving cars to the public for the following important reasons:

• Millions of lives saved. Although technology has reduced the highway fatality rate tenfold since Henry Ford’s day, the sheer ubiquity of cars means that, as Arthur C. Clarke wrote 30 years ago, they create “casualties on the same scale . . . as a small war.” The more than 1.3 million people killed and 50 million injured in traffic accidents worldwide each year can be expected to double in the next two decades as the number of vehicles doubles.

The introduction of self-driving cars would reduce the number of traffic accidents and fatalities immediately, not just when everyone has one, because they are programmed to avoid accidents with human drivers who may be drunk, sleepy, angry, inattentive, unskilled or texting, which collectively cause more than 95% of accidents world-wide. An NHTSA study released last year using data culled from black boxes in random car crashes revealed that only 1% of drivers fully applied the brakes and one-third didn’t brake at all. Robo-car will brake fully, every time.

• Enriched lives for the disabled and the elderly. Self-driving cars will increase freedom and lower the cost of mobility for the world’s 40 million blind, the 1 billion disabled and 100 million over 80 years of age, many of the latter housebound because they can’t pass driving tests. The aged cohort will rise fourfold in a few decades.

• Less wasted time. Self-driving cars are functionally the same as a personal commuter train that’s door-to-door. There is no more cost-efficient solution to urban congestion. The average commuter in America consumes each year 2 weeks of waking life driving. (Traffic wastes fuel too, but time is our most precious resource.)

• Revitalized cities. Self-driving cars boost road capacity by up to 300%, and eliminate congestion and the need for downtown parking spaces because the cars park themselves remotely. Planners will be able to radically reshape city landscapes, freeing up space for parks, trees and shops.

Reaping these benefits doesn’t require taxes or stimulus. To prime the pump, we need early adopters, as with the personal computer and cellphone revolutions. The people who flock to cutting-edge technologies will flock to buy self-driving cars if they’re offered. Millions already trust autonomous technology in the flight decks of commercial aircraft.

Lawyers and liability issues present another roadblock to deployment. Self-driving cars shift liability for accidents from people, with relatively shallow pockets, to the deep pockets of manufacturers. But we’ve dealt with this kind of challenge in liability law before, notably with vaccines.

You can’t sue Mother Nature if you get the flu, but you used to be able to sue a manufacturer for a vaccine’s side effect even if that vaccine technology saved millions of lives. An explosion in vaccine lawsuits resulted in only one U.S. company still producing the diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccine by 1984, with other vaccines on the same trajectory. So Congress passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act in 1986 protecting manufacturers of properly made vaccines. This was paired with a Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and a National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program for the few individuals who suffered side effects.

The self-driving car solution is clear. Congress should pre-empt NHTSA and the trial lawyers and pass a National Autonomous Vehicle Injury Act. The Fords and Nissans and Googles and Qualcomms should voluntarily create an Autonomous Vehicle Event Reporting System. And industry players should also create a National Autonomous Vehicle Compensation System. (Vaccine compensation is funded with a de minimis tax on each dose.)

Last November, NHTSA Administrator David Strickland told Congress that “in addition to the devastation” that “crashes cause to families, the economic costs to society reach into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Automated vehicles can potentially help reduce these numbers significantly.”

That potential has already been realized, whether regulators understand it or not. If the human toll from highway accidents were a disease and we knew there was a cure, it would be immoral not to marshal every corner of government and industry to deploy it.